Darfur

Photo: A group of women ride donkeys on their way to farm land near Um baru, North Darfur during the rainy season. Women, children and elder people often work in fields near displacement camps to avoid rapes and robberies. (Hamid Abdulsalam, UNAMID)

This historical overview provides a contextual background for understanding the issues Operation Broken Silence works on. It is part of our resource list for students, teachers, and the curious and was last updated January 2024. For more information about what's happening in Sudan and our work, please sign up for our email list.

Introduction

While the history of Darfur stretches back centuries, this overview focuses on the time period after Sudan’s independence in 1956. A chronological examination of the Darfur region in the contemporary era can be broken out into five main periods:

Pre-Modern & Colonial Background: 1200 BCE-1956 CE

Instability & Rising Tensions: 1956-1988

Rise of the Bashir Regime & Intercommunal Violence: 1989-2000

The Darfur Genocide (Part 1): 2001-2008

The Darfur Genocide (Part 2): 2009-2019

A summary of the post-2019 situation in Darfur is provided at the end as well.

Map: Location of Darfur. (Operation Broken Silence)

Photo: “Young Girl from Darfur” by Pierre Trémaux (circa 1855) is thought to be one of the first photographs highlighting Darfur.

Pre-Modern & Colonial Background: 1200 BCE-1956 CE

Darfur has an ancient history that offers few details, with the first known peoples belonging to several distinct ethnicities and related languages of the Daju people. Ancient Egyptian texts suggest an established Daju kingdom existed in the Marrah Mountains (present day central Darfur) as early as the 12th century BCE.

Although the geographic area known as Darfur has been inhabited for millennia, little direct documentation of life here is mentioned before 1600 CE, when more detailed information becomes available as the Fur people rose to power in Darfur. This undocumented history likely has roots in just how isolated the region has often been. Even today, archeological efforts in Darfur have been extremely minimal when compared to other parts of the world —despite potential excavation sites being known— leaving much of the region’s ancient and pre-modern historical understanding to tradition.

It is important to note that this isolation does not remove the historical causes of recent trouble in the region. Attacks on Darfur’s rich, diverse cultural tapestry by national military regimes in Khartoum, including the crime of genocide, have entrenched real historical grievances in countless communities.

Depending on who you ask, Darfur is home to between 36-80 tribes and ethnic groups that fall within the broader categories of African and Arab. The word Darfur refers to the region’s largest African ethnic group: the Fur. The first known historical mention of the Fur was in a 1664 account by Johann Michael Vansleb, a German theologian and traveler who was visiting Egypt. The Arabic word dar can be translated literally as home or house. Darfur then can be translated as home of the Fur.

Photo: Sudan's flag raised at the independence ceremony in January 1, 1956 by Prime Minister Ismail al-Aazhari and opposition leader Mohamed Ahmed al-Mahjoub. (Sudan Films Unit, Wikimedia Commons)

The vast majority of Darfuris are Muslim. A small Christian minority resides in Darfur, but estimates on the size of this community vary as many churches have met secretly in homes due to government persecution.

In 1899, the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium administrated Sudan as a colony. The joint British and Egyptian colonial government invested heavily in the Arab-dominated central and eastern parts of the country. Like other periphery regions of Sudan, Darfur was largely marginalized and ignored. The region was officially integrated into Sudan under colonial rule during World War I.

Shortly after Sudan’s independence on January 1, 1956, African Darfuri civil society groups advocated for a larger role in the country. Like many of Sudan’s ethnically African minorities, these groups were increasingly ignored by Arab-dominated governments in Khartoum. This led to mistrust between the country's powerful center and large swaths of Darfur and growing outside pressures on the region, both of which helped to set the stage for armed conflict that continues today.

Instability & Rising Tensions: 1956-1988

Map: Darfur’s porous borders have exacerbated local issues for decades, bringing weapons, armed groups, and Arab settlers into the region. (Operation Broken Silence)

Following Sudan's independence, African tribal groups in Darfur witnessed growing tension with Arab-dominated governments in Khartoum. The violent ideologies of Arabization and Islamization gained stronger traction in Sudan’s center. From the 1960s forward, Arab tribal groups in Darfur expanded their influence both within and outside of Darfur’s borders. Arab tribesman from across the Sahel also began settling in Darfur, often times near or on land belonging to ethnically African groups like the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa.

Changing regional dynamics between Sudan, Libya, and Chad pressed in on the region during these years. Darfur became a safe haven for Arab rebel groups fighting in Chad, with the governments of Sudan and Libya directly engaged on and off again in that conflict.

The situation in Darfur began to destabilize more rapidly in the 1980s. A horrific famine gripped the region and the Sudanese government was increasingly supporting Arab tribes in Darfur, who were seen as allies with the country's Arab political power base in Khartoum.

By the late 1980s, Darfur was awash in weapons after years of various government and rebel activities involving Sudan, Chad, Libya, and the Central African Republic and settlers from other countries across the Sahel.

Rise of the Bashir Regime & Intercommunal Violence: 1989-2000

In 1989, Colonel Omar al-Bashir and the National Islamic Front seized power in a military coup. Bashir took the titles of president, chief of state, prime minister, and chief of the armed forces. Wielding a Koran and an AK-47 rifle in Khartoum, Bashir declared to soldiers that he was going to reengineer the country into one dominated by an ethnic Arab elite and ruled by oppressive Islamic law.

Between 1989-1991, Bashir consolidated control over the government by banning trade unions, political parties, and other non-religious institutions. Over 70,000 members of the army, police, and civil administration were purged. The regime began to recruit, train, and arm Arab tribal militias in Darfur. This highlights a step in the 10 Stages of Genocide.

In 1991, Sudan's civil war in southern Sudan briefly spilled into Darfur. An armed southern rebel unit entered Darfur in an attempt to spread resistance to the Bashir regime. The southern rebel force was defeated by the Sudanese army and their Arab militia allies. African Darfuri communities seen as sympathetic to the plight of their southern neighbors were attacked and destroyed, a grim warning of what was to come a decade later.

In 1994, the Bashir regime divided Darfur into three federal states to hinder Darfuri African tribes, predominantly the Fur, from effectively mobilizing in support of ideas and policies that countered the regime.

As the century came to a close, war between large swaths of Darfur and the Bashir regime was becoming inevitable. Arab militias armed by the regime attacked Fur and Masalit communities at an alarming rate, causing the Fur and Masalit to self-arm. Clashes between both sides increased in scope and severity due to a number of decades-old issues including Arab racism against Africans, land use, basic rights, and access to markets.

Masalit fighters briefly gained the upper hand in 1999 by killing several Arab militia leaders who had led attacks on their communities. The Bashir regime responded by sending in the Sudanese army to arrest, imprison, and torture Masalit intellectuals and leaders and destroy Masalit villages.

In 2000, the brewing crisis reached the tipping point. A group of future Darfuri rebel leaders published The Black Book, a dissident piece of literature outlining Arab and regime abuses against African Darfuris. The Bashir regime failed to suppress The Black Book and talk of armed rebellion spread across Darfur.

Photo: A member of the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), one of the main armed rebel groups in Darfur that formed after years of regime oppression. (Hamid Abdulsalam, UNAMID)

The Darfur Genocide (Part 1): 2001-2008

As the world entered a new millennium, Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa leaders organized their fighters into rebel groups. The largest two were the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) and Justice & Equality Movement (JEM).

From 2001-2002, African Darfuri rebels attacked small regime army outposts, police stations, and Arab militias. Verbal threats from Bashir and regime counteroffensives failed to quell the rebellion. With the civil war in southern Sudan and genocide in the Nuba Mountains ongoing, the Sudanese army was ill-prepared to fight in Darfur. Regime soldiers were also facing a new kind of war in Darfur: semi-desert warfare, which was highlighted by fast-moving vehicles and hit-and-run tactics.

The Bashir regime began bombing known rebel bases and unarmed villages in the central Marrah Mountains, but failed to slow the speed at which the rebellion was catching on.

Early on the morning of April 25, 2003, organized SLA and JEM rebels entered El Father, the capital of North Darfur, home to a critical regime military base. The following four hour-long rebel assault saw seven Antonov bombers and helicopters destroyed and over 100 regime troops and pilots killed or captured, including the base commander.

The success of the rebel raid on such a critical regime military base was unprecedented. The Bashir regime would no longer ignore growing armed resistance to their iron-fisted rule.

Map: The Marrah Mountains have been a rebel-stronghold in Darfur for years. Regime forces have been unable to take control of the area, so government warplanes and artillery units have frequently targeted villages here. (Operation Broken Silence)

As government warplanes intensified bombings of unarmed African communities and rebel positions, the Bashir regime started to mass recruit, arm, and train large numbers of militiamen from several Arab tribes. The militias would become known as the Janjaweed, or devil on horseback. They would become the backbone of the brutal killing machine that was about to be unleashed against African tribes who formed the core of armed opposition groups - primarily the Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit.

Initial Janjaweed recruits to the government's war and genocide in 2003 came mainly from two Arab groups - herders from North Darfur and immigrants/mercenaries from Chad. While some Arab communities remained neutral, specifically those who owned land, Sudanese government promises of war loot and new land encouraged thousands of young Arab men to join the Janjaweed.

By the end of 2003, large numbers of Janjaweed units mounted on horseback had unleashed a scorched-earth campaign against Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit communities across Darfur. They destroyed everything that made life possible, including clean water wells, orchards, markets, and mosques.

The Janjaweed’s campaign inflicted death, displacement, and destruction on a shocking scale. Tens of thousands of civilians were killed and entire villages were razed to ground in the first few years of the genocide. Another two and a half million were driven into displacement camps, where small contingents of African Union peacekeeping troops —who had deployed into Darfur in 2006– had neither the mandate nor the resources to protect terrified Darfuris. More than 200,000 refugees fled across the border into Chad.

In 2004, senior U.S. government officials began describing the crisis as a genocide committed by the Bashir regime against African Darfuri groups.

Photo: A rebel fighter examines a burnt animal in Tukumare, north Darfur. The village was abandoned after clashes between the Sudanese army/Janjaweed and Darfuri rebels. (Albert Gonzalez Farran, UNAMID)

The genocide turned the tide of the war in favor of the regime. Darfuri rebel groups fractured underneath the Janjaweed’s widespread crimes and regime manipulation. The SLA and JEM’s guerrilla tactics remained an effective strategy; however, it did little to slow down the Janjaweed, who often times responded to rebel attacks by massacring entire Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit villages.

In March 2005, the United Nations Security Council referred the human rights catastrophe in Darfur to the International Criminal Court.

The Bashir regime and a faction of the SLA signed the Darfur Peace Agreement in May 2006 after seven rounds of African Union-led negotiations. JEM and another SLA faction refused to sign, saying compensation guarentees and the disarmament of the Janjaweed needed to be prioritized in any agreement.

A handful of other individual rebel commanders and splinter groups signed Declarations of Commitment to the agreement. Some were then armed by the regime and turned against their former allies, especially in North Darfur. The regime’s divide-and-conquer strategy had an expanding number of rebel groups fighting each other and the Janjaweed. Meanwhile, daily aerial bombings of communities continued paving the way for Janjaweed units to pillage, rape, and kill on a horrifying scale.

In mid-2006, the Bashir regime ordered the military back to the frontlines in a new offensive against rebel groups who had not signed the Darfur Peace Agreement. For a brief time, many Darfuri rebel groups put aside their differences to fend off the army’s renewed invasion of Darfur. This short-lived alliance between over a dozen Darfuri rebel factions was effective in helping the armed groups survive, but the army’s offensive proved disastrous for ordinary Darfuri communities.

Photo: Ahmed Haroun, the former Sudanese junior interior minister responsible for the western Darfur region was named as a suspect for war crimes in Darfur by the International Criminal Court's prosecutor, Feb. 27, 2007, gives a press conference at the presidential palace in Khartoum, Sudan in this 2006 file photo. Harun and a janjaweed militia leader, Ali Mohammed Ali Abd-al-Rahman, also known as Ali Kushayb, were suspected of a total of 51 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity, according to prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo. (AP Photo/Abd Raouf)

By September 2006, Darfur had become one of the greatest humanitarian catastrophes in the world. Hundreds of thousands of innocent people were out of reach of humanitarian aid due to expanding Janjaweed violence. With accusations of a government-backed genocide on the rise, the United Nations began working with the African Union to replace and enhance the weak international presence in Darfur.

In 2007, the International Criminal Court issued global arrest warrants for Ahmed Haroun, a senior regime official, and Ali Kushayb, a high-ranking Janjaweed leader, on dozens of counts of war crimes. In 2008, the court would also issue an arrest warrant for dictator Omar al-Bashir.

Meanwhile, the small African Union peacekeeping force in Darfur could barely protect itself, much less millions of terrified Darfuris seeking protection from the Janjaweed. By May of 2007, the peacekeeping force was on the verge of collapse due to a lack of resources and a hostile environment. The force would be transitioned to a stronger, United Nations-led command in 2008 called the United Nations - African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID). Thousands of international peacekeeping reinforcements would soon arrive in Darfur.

As Darfur continued to burn, the Bashir regime began resettling Arab tribes into areas of Darfur that had been "cleansed" of the African Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit tribes. This highlights another step in the 10 Stages of Genocide.

Photo: A woman rides a donkey while UNAMID troops from Tanzania conduct an armed patrol in South Darfur. (Albert Gonzalez Farran, UNAMID)

The Darfur Genocide (Part 2): 2009-2019

By 2009, it was clear that international efforts to save lives in Darfur were facing serious challenges from the Bashir regime. UNAMID peacekeeping patrols were being blocked by regime soldiers and Janjaweed militias. Mass violence had eased, but peacekeepers could often not access areas of Darfur where conflict remained ongoing. The Janjaweed and other regime-armed Arab groups continued to settle on land that the African Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit tribes had been driven off of.

Things only got worse in March of 2009, when the Bashir regime expelled international aid organizations from Darfur. This left hundreds of thousands of the most vulnerable people with little to no international support.

Under intense pressure from the Bashir regime, United Nations peacekeeping officials took a series of devastating steps that undermined the integrity of UNAMID’s mission. Rather than challenging ongoing regime war crimes being reported by their peacekeepers, UN officials began covering them up as early as 2009. Whistleblowers from within the peacekeeping mission emerged to decry these actions. UN officials took no concrete steps to address them.

It’s also during this period that Darfur began to fall out of the international spotlight. South Sudan’s upcoming independence and new crises coming out of the Arab Spring pulled the world’s attention away. UNAMID peacekeepers continued to struggle to provide security to all of Darfur’s persecuted African tribal groups; however, the mere presence of the peacekeeping force kept much of the large-scale fighting and attacks on communities at bay in areas that had a UNAMID presence.

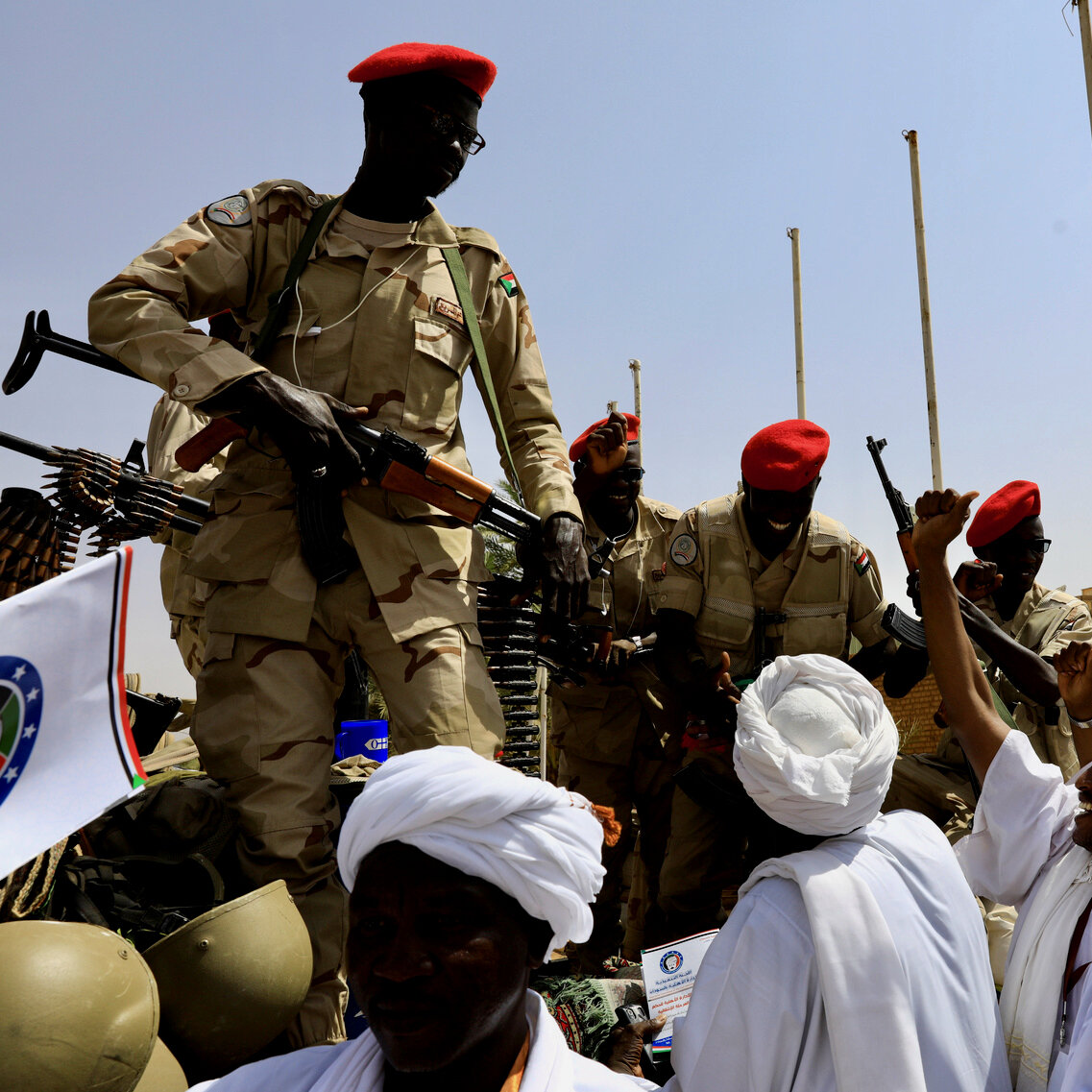

Photo: Rapid Support Forces paramilitaries dismount from their vehicle in Khartoum. (Umit Bektas/Adobe)

In 2013, the regime rebranded the Janjaweed as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and began outfitting the force with better equipment. Over the next few years, the RSF grew in size and strength, both by direct support from the regime and by using stolen land to mine gold, herd livestock, and more.

A grim warning of the RSF’s growing strength came in 2014, when the group launched a devastating assault on the rebel stronghold ofJebel Marra in central Darfur. While the brazen offensive failed to dislodge the rebels, the RSF forcibly displaced nearly 500,000 people in less than a month. The RSF’s new arsenal was on full display as well. Horses had been traded for modified SUVs with mounted machine guns. AK47s were supplemented with artillery, rocket-propelled grenades, and anti-aircraft guns.

Most concerning though was the increased international presence in the rank and file of the RSF. Survivors of RSF attacks noted that some of the paramilitaries were not Sudanese, but had come from neighboring Chad and Central African Republic. Islamist fighters from as far away as Mali had also entered the RSF’s ranks.

Over the next several years as the RSF grew in size, the paramilitary force spread to other hot spots in Sudan and beyond. RSF troops have committed mass war crimes in the southern Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile regions and have also popped up in major cities across Sudan. RSF units have also been implicated in illegal activity and war crimes in eastern Chad, the Central African Republic, and Yemen. The primary driver of on-the-ground violence in Darfur was now touching more and more aspects of daily life across Sudan.

Darfur Today (2019- Present)

In 2019, a civilian revolution swept across Sudan, leading to dictator Omar al-Bashir being overthrown by his own generals in April of that year. Following a horrific massacre by the RSF of peaceful protesters in Khartoum in June, renewed protests surged across Sudan and forced the regime to the negotiating table. A transitional government that was supposed to move the country toward free elections, democracy, and protection of basic human rights was implemented.

The transitional government was overthrown by surviving regime forces in October 2021. Leading the coup were the Sudanese army and RSF, two uneasy allies whose generals never saw eye-to-eye. Commanders in both organizations desired to see themselves as Sudan’s new ruling junta, with other armed regime groups beneath them.

From the time of the coup to early 2023, conditions in Sudan deteriorated on almost fronts. Inflation surged, peaceful protests resumed, humanitarian needs spread, and the web of oppression that transitional civilian leaders had been lifting was reinforced.

The RSF used this time to double down on becoming a self-sustaining force in Sudan, with Darfur as their stronghold. RSF generals fully secured their own weapons supply lines, launched international diplomatic efforts, entrenched themselves further in Darfur’s gold-mining sector, and began recruiting more fighters, both within Sudan and from other countries across the Sahel region. These actions almost always came at the expense of ordinary Sudanese, especially ethnically African Darfuris- who faced increasing attacks by RSF soldiers and dwindling economic opportunities.

Photo: A “Darfur Women Talking Peace” event at Al Salam displaced persons camp in El Fasher, North Darfur. Locally-led efforts like these to solve ongoing issues in Darfur continue to be blunted by RSF brutality. (Mohamad Almahady, UNAMID)

It also deteriorated the RSF’s tenuous relationship with the more dominant army, to the point of collapse. With long-promised progress on deeply-rooted fractures in Darfur elusive, evidence began to emerge as early as 2021 that Darfur was hurtling toward a new crisis.

The new war came on April 15, 2023. The RSF launched multiple attacks on army bases across Darfur and other regions of Sudan and attempted to seize government buildings in Khartoum. The lightening strike failed to knock the army out of power, with army units across the country putting up stiff resistance and bombing civilian areas RSF units attacked from. Both sides have engaged in large-scale war crimes, with the RSF using the fog of war to double down on their genocide of ethnic African minorities in Darfur.

While virtually every corner of Darfur has been negatively impacted by RSF violence, West Darfur especially has faced the brunt of the paramilitary force’s racism and brutality. Widespread genocidal massacres of the Masalit people group by the RSF and their local Arab allies abound. Tribal leaders and survivors of a two month-long massacre of the Masalit people in the city of El Geneina reported in June 2023 that over 10,000 of their people were killed in the city. Satellite imagery has confirmed entire neighborhoods and villages in West Darfur have been burned to the ground.

By the end of October 2023, most of Darfur had fallen under the control of the RSF. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of lives are in immediate danger. The crimes that began in Darfur over two decades ago are now being visited on much of Sudan, and the RSF is destroying the very government that created it.

The RSF and Darfur genocide highlight the interlinked issues of violence and silence across the country. The wars and attempted genocides in the Nuba Mountains, which the RSF has also participated in, highlight the structural issues of violence perpetuated by the regime. Due to the isolated location of both Darfur and the Nuba Mountains, violence and humanitarian blockades against ethnic minorities continue, and a lack of sustained media attention has kept the crises in Sudan from receiving the international attention they deserve.

The army-RSF war continues today and Darfur’s ethnic minorities are under siege. For more up to date information on the situation in Darfur and across Sudan, please visit our blog and sign up for our email list.

From Learning To Action

Our free global event turns everyday runs, bike rides, and walks into lifesaving support. Every mile you put in and dollar you raise helps fund emergency aid, healthcare, and education programs led by Sudanese heroes. We also have an option where you can skip the exercise and just fundraise. Every dollar raised makes a difference.

Checks can be made payable to Operation Broken Silence and mailed to PO Box 770900 Memphis, TN 38177-0900. You can also donate stock or crypto. Operation Broken Silence a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Donations are tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law. Our EIN is 80-0671198.