News & Updates

Check out the latest from Sudan and our movement

Make your last gift of 2023

We’re hoping to send another round of emergency funding to our Sudanese partners before year’s end. Your gift can help make that happen.

Friends and supporters,

It has been both a difficult and remarkable year in Sudan. Difficult in that the regime’s civil war has inflicted unprecedented death and destruction on the Sudanese people. Remarkable in that we’ve seen more bravery, love, and grit in our Sudanese partners than ever before.

Giving deadlines are below, but we encourage you to make your final gift of 2023 now. We need to send another round of emergency funding to our Sudanese partners in early January. Your gift can help make that happen and is tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law.

$1,000 - Fully funds one classroom at Endure Primary School in Yida Refugee Camp for half a semester.

$500 - Delivers food to Darfuri genocide survivors who have fled to South Sudan.

$250 - Provides a daily breakfast to 10 children for an entire month in Adré refugee camp, where many Darfuri genocide survivors now live.

$100 - Supports the monthly work of a sexual assault counselor in Zamzam displacement camp in North Darfur, Sudan.

$50 - Helps repair classrooms in Yida damaged by seasonal rains and provide for general maintenance.

Giving Season Deadlines

For gifts to count toward the 2023 tax year:

Online Donations - Sunday, Dec 31

Checks - Dated & postmarked by Friday, Dec 29. Make payable to Operation Broken Silence and mail to PO Box 770900 Memphis, TN 38177-0900.

Donor-Advised Funds - Ask your DAF manager for grant submission cutoff times. It usually takes several days for DAFs to process grants. We recommend submitting your donation now.

Stocks & Mutual Funds - Must be processed by close of markets on Friday, Dec 29. To give from a mutual fund, download our Investment Fund Transfer Form and follow the instructions. Please note that all stock and mutual fund donations are nonrefundable.

Cryptocurrency - Must be processed by midnight on Sunday, Dec 31. Blockchain processing times vary, so we encourage you to donate by December 30 to ensure adequate time for your gift to process. Please note that all crypto donations are nonrefundable.

Have a question before giving? Shoot us a message here and we’ll be in touch soon. With your generous support, we can help our Sudanese partners continue saving and change lives for the better.

Giving Tuesday 2023

You raised and gave over $15,000 for Sudanese heroes this Giving Tuesday! Learn more.

Friends and supporters,

Your generosity on this year’s Giving Tuesday was simply incredible. Donations are still trickling in, but as of today you raised and gave $15,261 across all of our primary and private campaigns. Well done!

Next week, the support you’ve provided will be sent to the education, healthcare, and emergency response programs we assist in Sudan. The ongoing war has made the work of the Sudanese heroes we partner with even more important than it already was. You are proving that when we pool our resources together, we can help them do amazing things for the people they serve. Thank you for an incredible day of generosity!

To learn more about the Sudanese heroes we support and see the latest news from them, we encourage you to visit our programs page.

The Giving Season

There is still much work to be done in these final days of 2023. Join us by giving once or through The Renewal, our family of monthly givers:

$200: Supports a teacher for one month.

$150: Pays a nurse assistant’s salary for an entire month.

$100: Provides pencils, notebooks, and other basic school supplies for 16 students.

$50: Gives nets, balls, and more play.

Checks can be made payable to Operation Broken Silence and mailed to PO Box 770900 Memphis, TN 38177-0900. You can also donate stock or crypto.

Your donation is tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law. Please keep your email donation receipt as your official record.

Women and Conflict in Sudan

Learn about how the crisis in Sudan impacts the lives of ordinary women.

This is a brief article providing a contextual background for understanding the issues Operation Broken Silence works on. It is part of our resource list for students, teachers, and the curious and was last updated November 2023. For more information about what's happening in Sudan and our work, please sign up for our email list.

While violence touches everyone in conflict, women and girls face particular gendered violence on top of genocidal violence from their national, ethnic, racial, or religious identity. Historically men are more likely to be victims of direct killing acts while women face non-killing acts that can be overlooked, obscured, and erased from the historical record.

While some advances have been made for women —with the International Criminal Court recognizing women’s experiences as convictable war crimes— there is still more work to be done by both further advocating for women’s voices during war tribunals and removing stigma of gender violence, so women feel comfortable sharing about their experiences.

Because of this stigma, oftentimes few stories exist, which is the case for women in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan. Over the past few decades, specific instances of gender violence include forced marriages, forced relocation to Khartoum, and the mass rape of women. All of these examples break down the fundamental bond of the family and community in the Nuba Mountains.

Below is a list of further resources on the violence that women face in conflict and genocide as well as how we might enact change to stop it.

Women’s Experiences of Genocide

Resource from The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

SUDAN - UN WOMEN

Article from the United Nations

RAPE IS A WEAPON OF WAR

Report from Amnesty International on sexual violence in Darfur

Celebrating Women’s History in Sudan

Article from Radio Dabanga

Ending Violence Against Women

Resource from the United Nations

GENOCIDE BY ATTRITION

Book with female experiences specific to the Nuba Mountains

From Learning To Action

Operation Broken Silence is building a global movement to empower Sudanese heroes in the war-torn periphery regions of Sudan, including teachers in Yida Refugee Camp. Teachers just like Chana.

The Endure Primary and Renewal Secondary Schools we sponsor are run entirely by Sudanese teachers. These are two of the only Nuba schools that require half of all students be girls. Your gift will help pay educator salaries, deliver school supplies and more.

If you can’t donate right now, we encourage you start a fundraising page and ask friends and family to give!

We are a 501(c)3 tax-exempt organization. Your donation is tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law.

The Dangers of Genocide Denial

Genocide denial is the attempt to minimize or redefine the scale and severity of a genocide, and sometimes even deny a genocide is or was being committed.

Photo: A home in Sudan’s Nuba Mountains smolders after being bombed by a regime warplane. The Sudanese government has denied committing two genocides in the region. (Operation Broken Silence)

This is a brief article providing a contextual background for understanding the issues Operation Broken Silence works on. It is part of our resource list for students, teachers, and the curious and was last updated November 2023. For more information about what's happening in Sudan and our work, please sign up for our email list.

Genocide denial is the attempt to minimize or redefine the scale and severity of a genocide, and sometimes even deny a genocide is or was being committed. It is the final stage of The 10 Stages of Genocide, a processual model that aims to demonstrate how genocides are committed.

The goal of genocide denial is twofold: cast doubt on charges of genocide to protect perpetrators and silence survivors. Genocide denial is an extended process that requires significant resources. It often begins before crimes are being committed and continues decades after the killing ends.

Examples of Genocide Denial

Campaigns of genocide denial are multi-faceted and cover a variety of actions. These are some of the common aspects that can be found in most genocide denials:

Redefining The Killing - Perpetrators and their enablers will often try to replace charges and accusations of genocide with a variety of terms, such as claiming that the killings are a “counter-insurgency” or civilians “caught in the crossfire” of a civil war. Sometimes perpetrators will even express false public remorse that civilians have been killed, but also claim that they were killed inadvertently.

Arguing Down The Numbers Of Those Killed - Human rights monitors, journalists, and other investigative entities usually don’t have full access to genocide-afflicted areas, so estimates of the number of people killed are often provided to the public. Perpetrators will often try to minimize the number of people who have been killed in the targeted group, knowing that date which is 100% accurate is not available to the world. For example, throughout the Darfur genocide, the Sudanese government regularly claimed that only 10,000 people had died, while evidence-based, conservative estimates stated over 250,000 people had been killed.

Victim Blaming - Perpetrators will often blame the victims, making false accusations that the aggressor was attacked first and they responded in “self-defense.” The most egregious perpetrators will claim that the victims “deserved it,” dehumanizing them even further to drive more killing and the silencing of survivors.

Denying Ongoing Killing - Genocide denial often starts before extermination begins, with the perpetrators brushing off concerns and warnings that a genocide they are preparing is imminent. Campaigns of denial are often become more elaborate when the killing begins. In rare moments of intense international focus, perpetrators will often deny committing or having specific knowledge of individual massacres they are accused of participating in.

Blocking Human Rights Investigations - Perpetrators will often block human rights monitors, journalists, and other investigative persons from entering afflicted areas. They will claim that outsiders are not allowed in because security is poor or blame the victim group, which may have self-armed to defend themselves. This prevents experts, humanitarian relief, and security assistance from reaching the most at-risk people and keeps the world in the dark on the specifics of a genocide.

Destruction of Evidence - Fearing criminal prosecution or an armed intervention by outside military forces, perpetrators will often dig up mass graves, burn the bodies, and try to cover up evidence and intimidate any witnesses. Documents and photographic evidence are sought out and destroyed. Lower-level perpetrators who carried out the killing face-to-face may be targeted by their commanders as part of the cover-up.

The Dangers of Genocide Denial

Genocide is a widespread enterprise, often involving tens of thousands of perpetrators up and down chains of command. Campaigns of genocide denial are rarely, if ever, successful in the long run. There are simply too many individual perpetrators involved to cover up every detail and shred of evidence, as well as survivors who have documented their own experiences.

Regardless, genocide denial still poses grave risks to victim groups and survivors, nation-states in which genocide has been committed, and international security.

Victim Groups and Survivors - Genocide denial is often painful to victim groups and survivors, even to generations who live after the crimes were committed. It is not just a denial of truth and reality, but also denies them the ability to heal, rebuild, and ease generational trauma. Research also suggests that one of the single best predictors of a future genocide is denial of a past genocide coupled with impunity for its perpetrators.

As long as the perpetrator group is in power, genocide denial provides an avenue to continue the genocide and prevent survivors and victims from finding paths forward. Yet even if perpetrators are removed from power, there are often still individuals and groups who rise up to deny a genocide. For example, Holocaust denialism still exists today despite the fall of Nazi Germany and the genocide being well-documented by the Nazis themselves.

Nation-States - Countries in which genocide has been committed and is being denied often face an array of challenges and threats in the aftermath. Large refugee and internally-displaced persons camps, devastated communities, poverty, insecurity, and more are left in the wake of a genocide. Societies are fractured and people groups –including bystanders– have lost trust in their neighbors.

Even if the perpetrator group has fallen from power, new governments often struggle to provide security, reparations, and truth and reconciliation processes to the citizenry. In some cases, genocide denial can lead to survivors taking matters into their own hands and committing revenge killings, which can lead to more genocidal massacres of the victim group.

International Security - The crime of genocide provides cover for other international crimes, such as weapons, human, and drug trafficking, wildlife poaching, and valuable natural resources being seized to fund more killing. Perpetrator militias and combatants may cross international borders to attack fleeing victims or help nearby allies, spreading chaos and insecurity as they go.

For example, Sudanese regime militias have fought in others wars in Libya, Central African Republic, and Yemen. They also control lucrative gold mines, cross international borders to poach endangered wildlife, and have participated in human and weapons trafficking networks. Their destabilizing impact has been felt throughout central, northern, and eastern Africa, not just in Sudan.

From Learning To Action

Operation Broken Silence is building a global movement to empower Sudanese heroes and genocide survivors in Sudan, including teachers in Yida Refugee Camp. Teachers just like Chana.

Operation Broken Silence is building a global movement to empower the Sudanese people through innovative programs as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Our work empowers Sudanese change makers and their critical efforts to save and change lives for the better.

There are three ways you can help. You can start a campaign and ask friends and family to give, setup a small monthly recurring donation, or make a generous one-time gift.

We are a 501(c)3 tax-exempt organization. Your donation is tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law.

Darfur

The history of the geographic region known as Darfur stretches back centuries. This overview focuses on the time period after Sudan’s independence in 1956.

Photo: A group of women ride donkeys on their way to farm land near Um baru, North Darfur during the rainy season. Women, children and elder people often work in fields near displacement camps to avoid rapes and robberies. (Hamid Abdulsalam, UNAMID)

This historical overview provides a contextual background for understanding the issues Operation Broken Silence works on. It is part of our resource list for students, teachers, and the curious and was last updated November 2023. For more information about what's happening in Sudan and our work, please sign up for our email list.

Introduction

While the history of Darfur stretches back centuries, this overview focuses on the time period after Sudan’s independence in 1956. A chronological examination of the Darfur region in the contemporary era can be broken out into five main periods:

Pre-Modern & Colonial Background: 1200 BCE-1956 CE

Instability & Rising Tensions: 1956-1988

Rise of the Bashir Regime & Intercommunal Violence: 1989-2000

The Darfur Genocide (Part 1): 2001-2008

The Darfur Genocide (Part 2): 2009-2019

A summary of the post-2019 situation in Darfur is provided at the end as well.

Map: Location of Darfur. (Operation Broken Silence)

Photo: “Young Girl from Darfur” by Pierre Trémaux (circa 1855) is thought to be one of the first photographs highlighting Darfur.

Pre-Modern & Colonial Background: 1200 BCE-1956 CE

Darfur has an ancient history that offers few details, with the first known peoples belonging to several distinct ethnicities and related languages of the Daju people. Ancient Egyptian texts suggest an established Daju kingdom existed in the Marrah Mountains (present day central Darfur) as early as the 12th century BCE.

Although the geographic area known as Darfur has been inhabited for millennia, little direct documentation of life here is mentioned before 1600 CE, when more detailed information becomes available as the Fur people rose to power in Darfur. This undocumented history likely has roots in just how isolated the region has often been. Even today, archeological efforts in Darfur have been extremely minimal when compared to other parts of the world —despite potential excavation sites being known— leaving much of the region’s ancient and pre-modern historical understanding to tradition.

It is important to note that this isolation does not remove the historical causes of recent trouble in the region. Attacks on Darfur’s rich, diverse cultural tapestry by national military regimes in Khartoum, including the crime of genocide, have entrenched real historical grievances in countless communities.

Depending on who you ask, Darfur is home to between 36-80 tribes and ethnic groups that fall within the broader categories of African and Arab. The word Darfur refers to the region’s largest African ethnic group: the Fur. The first known historical mention of the Fur was in a 1664 account by Johann Michael Vansleb, a German theologian and traveler who was visiting Egypt. The Arabic word dar can be translated literally as home or house. Darfur then can be translated as home of the Fur.

Photo: Sudan's flag raised at the independence ceremony in January 1, 1956 by Prime Minister Ismail al-Aazhari and opposition leader Mohamed Ahmed al-Mahjoub. (Sudan Films Unit, Wikimedia Commons)

The vast majority of Darfuris are Muslim. A small Christian minority resides in Darfur, but estimates on the size of this community vary as many churches have met secretly in homes due to government persecution.

In 1899, the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium administrated Sudan as a colony. The joint British and Egyptian colonial government invested heavily in the Arab-dominated central and eastern parts of the country. Like other periphery regions of Sudan, Darfur was largely marginalized and ignored. The region was officially integrated into Sudan under colonial rule during World War I.

Shortly after Sudan’s independence on January 1, 1956, African Darfuri civil society groups advocated for a larger role in the country. Like many of Sudan’s ethnically African minorities, these groups were increasingly ignored by Arab-dominated governments in Khartoum. This led to mistrust between the country's powerful center and large swaths of Darfur and growing outside pressures on the region, both of which helped to set the stage for armed conflict that continues today.

Instability & Rising Tensions: 1956-1988

Map: Darfur’s porous borders have exacerbated local issues for decades, bringing weapons, armed groups, and Arab settlers into the region. (Operation Broken Silence)

Following Sudan's independence, African tribal groups in Darfur witnessed growing tension with Arab-dominated governments in Khartoum. The violent ideologies of Arabization and Islamization gained stronger traction in Sudan’s center. From the 1960s forward, Arab tribal groups in Darfur expanded their influence both within and outside of Darfur’s borders. Arab tribesman from across the Sahel also began settling in Darfur, often times near or on land belonging to ethnically African groups like the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa.

Changing regional dynamics between Sudan, Libya, and Chad pressed in on the region during these years. Darfur became a safe haven for Arab rebel groups fighting in Chad, with the governments of Sudan and Libya directly engaged on and off again in that conflict.

The situation in Darfur began to destabilize more rapidly in the 1980s. A horrific famine gripped the region and the Sudanese government was increasingly supporting Arab tribes in Darfur, who were seen as allies with the country's Arab political power base in Khartoum.

By the late 1980s, Darfur was awash in weapons after years of various government and rebel activities involving Sudan, Chad, Libya, and the Central African Republic and settlers from other countries across the Sahel.

Rise of the Bashir Regime & Intercommunal Violence: 1989-2000

In 1989, Colonel Omar al-Bashir and the National Islamic Front seized power in a military coup. Bashir took the titles of president, chief of state, prime minister, and chief of the armed forces. Wielding a Koran and an AK-47 rifle in Khartoum, Bashir declared to soldiers that he was going to reengineer the country into one dominated by an ethnic Arab elite and ruled by oppressive Islamic law.

Between 1989-1991, Bashir consolidated control over the government by banning trade unions, political parties, and other non-religious institutions. Over 70,000 members of the army, police, and civil administration were purged. The regime began to recruit, train, and arm Arab tribal militias in Darfur. This highlights a step in the 10 Stages of Genocide.

In 1991, Sudan's civil war in southern Sudan briefly spilled into Darfur. An armed southern rebel unit entered Darfur in an attempt to spread resistance to the Bashir regime. The southern rebel force was defeated by the Sudanese army and their Arab militia allies. African Darfuri communities seen as sympathetic to the plight of their southern neighbors were attacked and destroyed, a grim warning of what was to come a decade later.

In 1994, the Bashir regime divided Darfur into three federal states to hinder Darfuri African tribes, predominantly the Fur, from effectively mobilizing in support of ideas and policies that countered the regime.

As the century came to a close, war between large swaths of Darfur and the Bashir regime was becoming inevitable. Arab militias armed by the regime attacked Fur and Masalit communities at an alarming rate, causing the Fur and Masalit to self-arm. Clashes between both sides increased in scope and severity due to a number of decades-old issues including Arab racism against Africans, land use, basic rights, and access to markets.

Masalit fighters briefly gained the upper hand in 1999 by killing several Arab militia leaders who had led attacks on their communities. The Bashir regime responded by sending in the Sudanese army to arrest, imprison, and torture Masalit intellectuals and leaders and destroy Masalit villages.

In 2000, the brewing crisis reached the tipping point. A group of future Darfuri rebel leaders published The Black Book, a dissident piece of literature outlining Arab and regime abuses against African Darfuris. The Bashir regime failed to suppress The Black Book and talk of armed rebellion spread across Darfur.

Photo: A member of the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), one of the main armed rebel groups in Darfur that formed after years of regime oppression. (Hamid Abdulsalam, UNAMID)

The Darfur Genocide (Part 1): 2001-2008

As the world entered a new millennium, Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa leaders organized their fighters into rebel groups. The largest two were the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) and Justice & Equality Movement (JEM).

From 2001-2002, African Darfuri rebels attacked small regime army outposts, police stations, and Arab militias. Verbal threats from Bashir and regime counteroffensives failed to quell the rebellion. With the civil war in southern Sudan and genocide in the Nuba Mountains ongoing, the Sudanese army was ill-prepared to fight in Darfur. Regime soldiers were also facing a new kind of war in Darfur: semi-desert warfare, which was highlighted by fast-moving vehicles and hit-and-run tactics.

The Bashir regime began bombing known rebel bases and unarmed villages in the central Marrah Mountains, but failed to slow the speed at which the rebellion was catching on.

Early on the morning of April 25, 2003, organized SLA and JEM rebels entered El Father, the capital of North Darfur, home to a critical regime military base. The following four hour-long rebel assault saw seven Antonov bombers and helicopters destroyed and over 100 regime troops and pilots killed or captured, including the base commander.

The success of the rebel raid on such a critical regime military base was unprecedented. The Bashir regime would no longer ignore growing armed resistance to their iron-fisted rule.

Map: The Marrah Mountains have been a rebel-stronghold in Darfur for years. Regime forces have been unable to take control of the area, so government warplanes and artillery units have frequently targeted villages here. (Operation Broken Silence)

As government warplanes intensified bombings of unarmed African communities and rebel positions, the Bashir regime started to mass recruit, arm, and train large numbers of militiamen from several Arab tribes. The militias would become known as the Janjaweed, or devil on horseback. They would become the backbone of the brutal killing machine that was about to be unleashed against African tribes who formed the core of armed opposition groups - primarily the Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit.

Initial Janjaweed recruits to the government's war and genocide in 2003 came mainly from two Arab groups - herders from North Darfur and immigrants/mercenaries from Chad. While some Arab communities remained neutral, specifically those who owned land, Sudanese government promises of war loot and new land encouraged thousands of young Arab men to join the Janjaweed.

By the end of 2003, large numbers of Janjaweed units mounted on horseback had unleashed a scorched-earth campaign against Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit communities across Darfur. They destroyed everything that made life possible, including clean water wells, orchards, markets, and mosques.

The Janjaweed’s campaign inflicted death, displacement, and destruction on a shocking scale. Tens of thousands of civilians were killed and entire villages were razed to ground in the first few years of the genocide. Another two and a half million were driven into displacement camps, where small contingents of African Union peacekeeping troops —who had deployed into Darfur in 2006– had neither the mandate nor the resources to protect terrified Darfuris. More than 200,000 refugees fled across the border into Chad.

In 2004, senior U.S. government officials began describing the crisis as a genocide committed by the Bashir regime against African Darfuri groups.

Photo: A rebel fighter examines a burnt animal in Tukumare, north Darfur. The village was abandoned after clashes between the Sudanese army/Janjaweed and Darfuri rebels. (Albert Gonzalez Farran, UNAMID)

The genocide turned the tide of the war in favor of the regime. Darfuri rebel groups fractured underneath the Janjaweed’s widespread crimes and regime manipulation. The SLA and JEM’s guerrilla tactics remained an effective strategy; however, it did little to slow down the Janjaweed, who often times responded to rebel attacks by massacring entire Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit villages.

In March 2005, the United Nations Security Council referred the human rights catastrophe in Darfur to the International Criminal Court.

The Bashir regime and a faction of the SLA signed the Darfur Peace Agreement in May 2006 after seven rounds of African Union-led negotiations. JEM and another SLA faction refused to sign, saying compensation guarentees and the disarmament of the Janjaweed needed to be prioritized in any agreement.

A handful of other individual rebel commanders and splinter groups signed Declarations of Commitment to the agreement. Some were then armed by the regime and turned against their former allies, especially in North Darfur. The regime’s divide-and-conquer strategy had an expanding number of rebel groups fighting each other and the Janjaweed. Meanwhile, daily aerial bombings of communities continued paving the way for Janjaweed units to pillage, rape, and kill on a horrifying scale.

In mid-2006, the Bashir regime ordered the military back to the frontlines in a new offensive against rebel groups who had not signed the Darfur Peace Agreement. For a brief time, many Darfuri rebel groups put aside their differences to fend off the army’s renewed invasion of Darfur. This short-lived alliance between over a dozen Darfuri rebel factions was effective in helping the armed groups survive, but the army’s offensive proved disastrous for ordinary Darfuri communities.

Photo: Ahmed Haroun, the former Sudanese junior interior minister responsible for the western Darfur region was named as a suspect for war crimes in Darfur by the International Criminal Court's prosecutor, Feb. 27, 2007, gives a press conference at the presidential palace in Khartoum, Sudan in this 2006 file photo. Harun and a janjaweed militia leader, Ali Mohammed Ali Abd-al-Rahman, also known as Ali Kushayb, were suspected of a total of 51 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity, according to prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo. (AP Photo/Abd Raouf)

By September 2006, Darfur had become one of the greatest humanitarian catastrophes in the world. Hundreds of thousands of innocent people were out of reach of humanitarian aid due to expanding Janjaweed violence. With accusations of a government-backed genocide on the rise, the United Nations began working with the African Union to replace and enhance the weak international presence in Darfur.

In 2007, the International Criminal Court issued global arrest warrants for Ahmed Haroun, a senior regime official, and Ali Kushayb, a high-ranking Janjaweed leader, on dozens of counts of war crimes. In 2008, the court would also issue an arrest warrant for dictator Omar al-Bashir.

Meanwhile, the small African Union peacekeeping force in Darfur could barely protect itself, much less millions of terrified Darfuris seeking protection from the Janjaweed. By May of 2007, the peacekeeping force was on the verge of collapse due to a lack of resources and a hostile environment. The force would be transitioned to a stronger, United Nations-led command in 2008 called the United Nations - African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID). Thousands of international peacekeeping reinforcements would soon arrive in Darfur.

As Darfur continued to burn, the Bashir regime began resettling Arab tribes into areas of Darfur that had been "cleansed" of the African Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit tribes. This highlights another step in the 10 Stages of Genocide.

Photo: A woman rides a donkey while UNAMID troops from Tanzania conduct an armed patrol in South Darfur. (Albert Gonzalez Farran, UNAMID)

The Darfur Genocide (Part 2): 2009-2019

By 2009, it was clear that international efforts to save lives in Darfur were facing serious challenges from the Bashir regime. UNAMID peacekeeping patrols were being blocked by regime soldiers and Janjaweed militias. Mass violence had eased, but peacekeepers could often not access areas of Darfur where conflict remained ongoing. The Janjaweed and other regime-armed Arab groups continued to settle on land that the African Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit tribes had been driven off of.

Things only got worse in March of 2009, when the Bashir regime expelled international aid organizations from Darfur. This left hundreds of thousands of the most vulnerable people with little to no international support.

Under intense pressure from the Bashir regime, United Nations peacekeeping officials took a series of devastating steps that undermined the integrity of UNAMID’s mission. Rather than challenging ongoing regime war crimes being reported by their peacekeepers, UN officials began covering them up as early as 2009. Whistleblowers from within the peacekeeping mission emerged to decry these actions. UN officials took no concrete steps to address them.

It’s also during this period that Darfur began to fall out of the international spotlight. South Sudan’s upcoming independence and new crises coming out of the Arab Spring pulled the world’s attention away. UNAMID peacekeepers continued to struggle to provide security to all of Darfur’s persecuted African tribal groups; however, the mere presence of the peacekeeping force kept much of the large-scale fighting and attacks on communities at bay in areas that had a UNAMID presence.

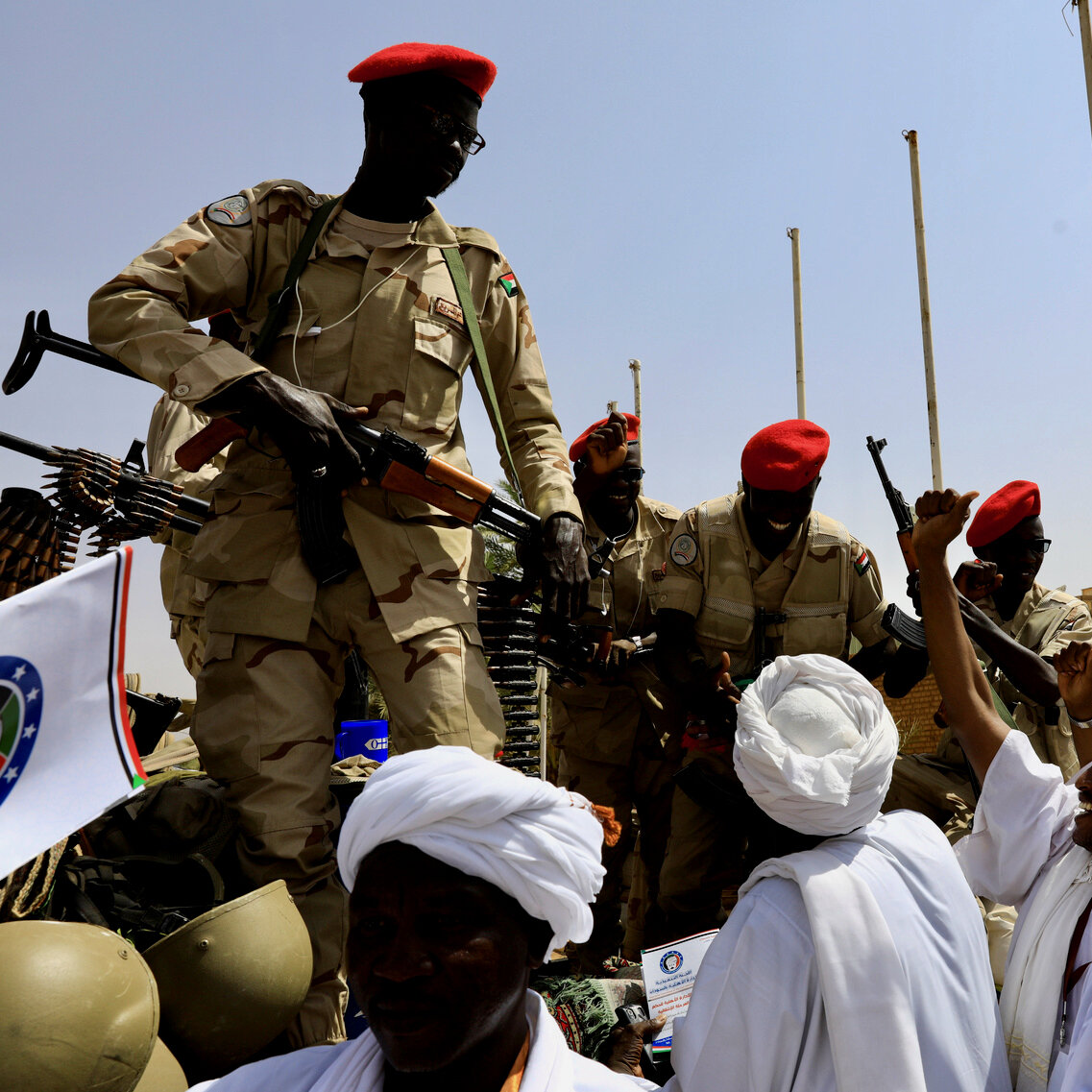

Photo: Rapid Support Forces paramilitaries dismount from their vehicle in Khartoum. (Umit Bektas/Adobe)

In 2013, the regime rebranded the Janjaweed as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and began outfitting the force with better equipment. Over the next few years, the RSF grew in size and strength, both by direct support from the regime and by using stolen land to mine gold, herd livestock, and more.

A grim warning of the RSF’s growing strength came in 2014, when the group launched a devastating assault on the rebel stronghold ofJebel Marra in central Darfur. While the brazen offensive failed to dislodge the rebels, the RSF forcibly displaced nearly 500,000 people in less than a month. The RSF’s new arsenal was on full display as well. Horses had been traded for modified SUVs with mounted machine guns. AK47s were supplemented with artillery, rocket-propelled grenades, and anti-aircraft guns.

Most concerning though was the increased international presence in the rank and file of the RSF. Survivors of RSF attacks noted that some of the paramilitaries were not Sudanese, but had come from neighboring Chad and Central African Republic. Islamist fighters from as far away as Mali had also entered the RSF’s ranks.

Over the next several years as the RSF grew in size, the paramilitary force spread to other hot spots in Sudan and beyond. RSF troops have committed mass war crimes in the southern Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile regions and have also popped up in major cities across Sudan. RSF units have also been implicated in illegal activity and war crimes in eastern Chad, the Central African Republic, and Yemen. The primary driver of on-the-ground violence in Darfur was now touching more and more aspects of daily life across Sudan.

Darfur Today (2019- Present)

In 2019, a civilian revolution swept across Sudan, leading to dictator Omar al-Bashir being overthrown by his own generals in April of that year. Following a horrific massacre by the RSF of peaceful protesters in Khartoum in June, renewed protests surged across Sudan and forced the regime to the negotiating table. A transitional government that was supposed to move the country toward free elections, democracy, and protection of basic human rights was implemented.

The transitional government was overthrown by surviving regime forces in October 2021. Leading the coup were the Sudanese army and RSF, two uneasy allies whose generals never saw eye-to-eye. Commanders in both organizations desired to see themselves as Sudan’s new ruling junta, with other armed regime groups beneath them.

From the time of the coup to early 2023, conditions in Sudan deteriorated on almost fronts. Inflation surged, peaceful protests resumed, humanitarian needs spread, and the web of oppression that transitional civilian leaders had been lifting was reinforced.

The RSF used this time to double down on becoming a self-sustaining force in Sudan, with Darfur as their stronghold. RSF generals fully secured their own weapons supply lines, launched international diplomatic efforts, entrenched themselves further in Darfur’s gold-mining sector, and began recruiting more fighters, both within Sudan and from other countries across the Sahel region. These actions almost always came at the expense of ordinary Sudanese, especially ethnically African Darfuris- who faced increasing attacks by RSF soldiers and dwindling economic opportunities.

Photo: A “Darfur Women Talking Peace” event at Al Salam displaced persons camp in El Fasher, North Darfur. Locally-led efforts like these to solve ongoing issues in Darfur continue to be blunted by RSF brutality. (Mohamad Almahady, UNAMID)

It also deteriorated the RSF’s tenuous relationship with the more dominant army, to the point of collapse. With long-promised progress on deeply-rooted fractures in Darfur elusive, evidence began to emerge as early as 2021 that Darfur was hurtling toward a new crisis.

The new war came on April 15, 2023. The RSF launched multiple attacks on army bases across Darfur and other regions of Sudan and attempted to seize government buildings in Khartoum. The lightening strike failed to knock the army out of power, with army units across the country putting up stiff resistance and bombing civilian areas RSF units attacked from. Both sides have engaged in large-scale war crimes, with the RSF using the fog of war to double down on their genocide of ethnic African minorities in Darfur.

While virtually every corner of Darfur has been negatively impacted by RSF violence, West Darfur especially has faced the brunt of the paramilitary force’s racism and brutality. Widespread genocidal massacres of the Masalit people group by the RSF and their local Arab allies abound. Tribal leaders and survivors of a two month-long massacre of the Masalit people in the city of El Geneina reported in June 2023 that over 10,000 of their people were killed in the city. Satellite imagery has confirmed entire neighborhoods and villages in West Darfur have been burned to the ground.

By the end of October 2023, most of Darfur had fallen under the control of the RSF. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of lives are in immediate danger. The crimes that began in Darfur over two decades ago are now being visited on much of Sudan, and the RSF is destroying the very government that created it.

The RSF and Darfur genocide highlight the interlinked issues of violence and silence across the country. The wars and attempted genocides in the Nuba Mountains, which the RSF has also participated in, highlight the structural issues of violence perpetuated by the regime. Due to the isolated location of both Darfur and the Nuba Mountains, violence and humanitarian blockades against ethnic minorities continue, and a lack of sustained media attention has kept the crises in Sudan from receiving the international attention they deserve.

The army-RSF war continues today and Darfur’s ethnic minorities are under siege. For more up to date information on the situation in Darfur and across Sudan, please visit our blog and sign up for our email list.

From Learning To Action

Operation Broken Silence is building a global movement to empower Sudanese heroes in the war-torn periphery regions of Sudan.

This is a very high-risk program that is severely underfunded. We are providing occasional updates and stories to our supporters so they can see their impact. Your gift will provide fuel for ground transports and food and other basic needs for refugees who reach South Sudan.

If you can’t donate right now, we encourage you start a fundraising page and ask friends and family to give!

We are a 501(c)3 tax-exempt organization. Your donation is tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law.

The 10 Stages Of Genocide

Genocide doesn't just happen in a vacuum. It is a crime that follows a largely predictable process.

Photo: Auschwitz II-Birkenau, a former Nazi concentration and extermination camp. Roughly 90% of the more one million victims of Auschwitz Concentration Camp died in Birkenau. More than nine out of every ten were Jews. A large proportion of the more than 70,000 Poles who died or were killed in the Auschwitz complex perished in Birkenau, as did approximately 20,000 Roma and Sinti, in addition to Soviet POWs and prisoners of other nationalities. (Canva Pro)

This is a brief article providing a contextual background for understanding the issues Operation Broken Silence works on. It is part of our resource list for students, teachers, and the curious and was last updated November 2023. For more information about what's happening in Sudan and our work, please sign up for our email list.

The 10 Stages of Genocide is a processual model that aims to demonstrate how the crime of genocide is committed. It is widely accepted as a helpful tool for understanding the mechanics of past genocides, as well as providing early warning signs that can be used to prevent future genocides and other mass atrocity crimes. It also provides preventive measures that can be used to prevent, slow, or stop the process.

Dr. Gregory Stanton (Genocide Watch)

Origin of the Model

This system was designed by Dr. Gregory Stanton, who has been deeply engaged in genocide prevention and justice efforts in governmental, academic, and civil society institutions since the 1980s.

Dr. Stanton best described how to use the 10 Stages of Genocide model. He wrote:

“No model is ever perfect. All are merely ideal-typical representations of reality that are meant to help us think more clearly about social and cultural processes. It is important not to confuse any stage with a status. Each stage is a process. It is like a fluctuating point on a thermometer that rises and falls as the social temperature in a potential area of conflict rises and falls. It is crucial not to confuse this model with a linear one. In all genocides, many stages occur simultaneously.”

Stage 1: Classification

All cultures have categories to distinguish people into “us and them” by ethnicity, race, religion, or nationality: German and Jew, Hutu and Tutsi. Bipolar societies that lack mixed categories, such as Rwanda and Burundi, are the most likely to have genocide.

One of the most important classifications in the current nation-state system is citizenship in a nationality. Removal or denial of a group's citizenship is a legal way to deny the group's civil and human rights. The first step toward the genocide of Jews and Roma in Nazi Germany were the laws to strip them of their German citizenship. Burma's 1982 citizenship law classified Rohingyas out of national citizenship. In India, the Citizenship Act denies a route to citizenship for Muslim refugees. Native Americans were not granted citizenship in the USA until 1924, after centuries of genocide that decimated their populations.

The main preventive measure at this early stage is to develop universalistic institutions that transcend ethnic or racial divisions, that actively promote tolerance and understanding, and that promote classifications that transcend the divisions. The Catholic church could have played this role in Rwanda, had it not been riven by the same ethnic cleavages as Rwandan society.

Promotion of a common language in countries like Tanzania has also promoted transcendent national identity. Laws that provide routes for citizenship to immigrants and refugees break down barriers to civil rights. This search for common ground is vital to early prevention of genocide.

Stage 2: Symbolization

We give names or other symbols to the classifications. We name people “Jews” or “Roma”, or distinguish them by colors or dress; and apply the symbols to members of groups. Classification and symbolization are universally human and do not necessarily result in genocide unless they lead to dehumanization.

When combined with hatred, symbols may be forced upon unwilling members of pariah groups: the yellow star for Jews under Nazi rule, the blue scarf for people from the Eastern Zone in Khmer Rouge Cambodia.

To combat symbolization, hate symbols can be legally forbidden (swastikas) as can hate speech. Group marking like gang clothing or tribal scarring can be outlawed, as well. The problem is that legal limitations will fail if unsupported by popular cultural enforcement. Though Hutu and Tutsi were forbidden words in Burundi until the 1980’s, code words replaced them.

If widely supported, denial of symbolization can be powerful, as it was in Bulgaria, where the government refused to supply enough yellow badges and at least 80% of Jews did not wear them, depriving the yellow star of its significance as a Nazi symbol for Jews.

Stage 3: Discrimination

A dominant group uses law, custom, and political power to deny the rights of other groups. The powerless group may not be accorded full civil rights, voting rights, or even citizenship.

The dominant group is driven by an exclusionary ideology that would deprive less powerful groups of their rights. The ideology advocates monopolization or expansion of power by the dominant group. It legitimizes the victimization of weaker groups. Advocates of exclusionary ideologies are often charismatic, expressing the resentments of their followers. Examples include the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 in Nazi Germany, which stripped Jews of their German citizenship, and prohibited their employment by the government and by universities. Discrimination against Native and African-Americans was enshrined in the US Constitution until the post-Civil War Amendments and mid-20th century laws to enforce them. Denial of citizenship to the Rohingya Muslim minority in Myanmar led to genocide in 2017 and the displacement of over a million refugees.

Prevention against discrimination means full political empowerment and citizenship rights for all groups in a society. Discrimination on the basis of nationality, ethnicity, race or religion should be outlawed. Individuals should have the right to sue the state, corporations, and other individuals if their rights are violated.

Stage 4: Dehumanization

One group denies the humanity of the other group. Members of it are equated with animals, vermin, insects or diseases.

Dehumanization overcomes the normal human revulsion against murder. At this stage, hate propaganda in print, on hate radios, and in social media is used to vilify the victim group. It may even be incorporated into school textbooks. Indoctrination prepares the way for incitement.

The majority group is taught to regard the other group as less than human, and even alien to their society. They are indoctrinated to believe that “we are better off without them.” The powerless group can become so depersonalized that they are numbers rather than names, as Jews were in the death camps. They are equated with filth, impurity, and immorality. Hate speech fills the propaganda of official radio, newspapers, and speeches.

To combat dehumanization, incitement to genocide should not be confused with protected speech. Genocidal societies lack constitutional protection for countervailing speech and should be treated differently than democracies. Local and international leaders should condemn the use of hate speech and make it culturally unacceptable.

Leaders who incite genocide should be prosecuted in national courts. They should be banned from international travel and have their foreign finances frozen. Hate radio stations should be jammed or shut down, and hate propaganda and its sources banned from social media and the internet. Hate crimes and atrocities should be promptly punished.

Stage 5: Organization

Genocide is always organized, usually by the state, often using militias to provide deniability of state responsibility (the Janjaweed in Darfur). Sometimes organization is informal (Hindu mobs led by local RSS militants) or decentralized (terrorist groups).

Special army units or militias are often trained and armed. Plans are made for genocidal killings. Genocide often occurs during civil or international wars. Arms flows to states and militias (even in violation of UN Arms Embargoes) facilitate acts of genocide. States organize secret police to spy on, arrest, torture, and murder people suspected of opposition to political leaders.

Motivations for targeting a group are indoctrinated through mass media and special training for murderous militias, death squads, and special army killing units like the Nazi Einsaztgruppen, which murdered 1.5 million Jews in Eastern Europe.

To combat organization, membership in genocidal militias should be outlawed. Their leaders should be denied visas for foreign travel and their foreign assets frozen. The UN should impose arms embargoes on governments and citizens of countries involved in genocidal massacres, and create commissions to investigate violations, as was done in post-genocide Rwanda. National legal systems should prosecute and disarm groups that plan and commit hate crimes.

Stage 6: Polarization

Extremists drive the groups apart. Hate groups broadcast polarizing propaganda. Laws may forbid intermarriage or social interaction.

Extremist terrorism targets moderates, intimidating and silencing the center. Moderates from the perpetrators’ own group are most able to stop genocide, so are the first to be arrested and killed. Leaders in targeted groups are the next to be arrested and murdered.

The dominant group passes emergency laws or decrees that grants them total power over the targeted group. The laws erode fundamental civil rights and liberties. Targeted groups are disarmed to make them incapable of self-defense, and to ensure that the dominant group has total control.

Prevention may mean security protection for moderate leaders or assistance to human rights groups. Assets of extremists should be seized, and visas for international travel denied to them. Coups d’état by extremists should be opposed by international sanctions and regional isolation of extremist leaders. Vigorous objections should be raised to arrests of members of opposition groups. If necessary, targeted groups should be armed to defend themselves. National government leaders should denounce polarizing hate speech. Educators should teach tolerance.

Stage 7: Preparation

National or perpetrator group leaders plan the “Final Solution” to the Jewish, Armenian, Tutsi or other targeted group “question.” They often use euphemisms to cloak their intentions, such as referring to their goals as “ethnic cleansing,” “purification,” or “counter-terrorism.”

They build armies, buy weapons and train their troops and militias. They indoctrinate the populace with fear of the victim group. Leaders often claim that “if we don’t kill them, they will kill us,” disguising genocide as self-defense. There is a sudden increase in inflammatory rhetoric and hate propaganda with the objective of creating fear of the other group.

Political processes such as peace accords that threaten the dominance of the ruling group through elections or prosecution for corruption may actually trigger genocide.

Prevention of preparation may include arms embargoes and commissions to enforce them. It should include prosecution of incitement and conspiracy to commit genocide, both crimes under Article 3 of the Genocide Convention.

National law enforcement authorities should arrest and prosecute leaders of groups planning genocidal massacres.

Stage 8: Persecution

Victims are identified and separated out because of their national, ethnic, racial, or religious identity. The victim group’s most basic human rights are systematically violated through extrajudicial killings, torture, and forced displacement. Death lists are drawn up.

In state-sponsored genocide, members of victim groups may be forced to wear identifying symbols. Their property is often expropriated. Sometimes they are segregated into ghettoes, deported to concentration camps, or confined to a famine-struck region and starved. They are deliberately deprived of resources such as water or food in order to slowly destroy the group. Programs are implemented to prevent procreation through forced sterilization or abortions. Children are forcibly taken from their parents.

Genocidal massacres begin. All of these are acts of genocide outlawed by the Genocide Convention. They are acts of genocide because they intentionally destroy part of a group.

The perpetrators watch for whether such massacres are opposed by any effective international response. If there is no reaction, they realize they can get away with genocide. The perpetrators know that the UN, regional organizations, and more powerful nations will again be bystanders and permit genocide.

At this stage, a Genocide Emergency must be declared. If the political will of great powers, regional alliances, or UN Security Council or General Assembly can be mobilized, vigorous diplomacy, targeted economic sanctions, and even armed international intervention should be prepared. Assistance should be provided to the victim group to prepare for its self-defense. Humanitarian assistance should be organized by the UN and private relief groups for the inevitable tide of refugees to come.

Stage 9: Extermination

Extermination begins and quickly becomes the mass killing legally called “genocide.” It is “extermination” to the killers because they do not believe their victims to be fully human.

When it is sponsored by the state, the armed forces often work with militias to do the killing.

The goal of total genocides is to kill all the members of the targeted group. But most genocides are genocides "in part." All educated members of the targeted group might be murdered (Burundi 1972). All men and boys of fighting age may be murdered (Srebrenica, Bosnia 1995). All women and girls may be raped (Darfur, Myanmar.) Mass rapes of women have become a characteristic of all modern genocides. Rape is used as a means to genetically alter and destroy the victim group.

Sometimes the genocide results in revenge killings by groups against each other, creating the downward whirlpool-like cycle of bilateral genocide (as in Burundi). Destruction of cultural and religious property is employed to annihilate the group’s existence from history (Armenia 1915 - 1922, Da'esh/ISIS 2014 - 2018).

“Total war” between nations or ethnic groups is inherently genocidal because it does not differentiate civilians from non-combatants. "Carpet" bombing, firebombing, bombing hospitals, and use of chemical or biological weapons are war crimes and also acts of genocide. Terrorism does not differentiate civilians and combatants, and when intended to destroy members of a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group is genocidal. Use of nuclear weapons is the ultimate act of genocide because it is consciously intended to destroy a substantial part of a national group.

During active genocide, only rapid and overwhelming armed intervention can stop genocide. Real safe areas or refugee escape corridors should be established with heavily armed international protection. (An unsafe “safe” area is worse than none at all.)

For armed interventions, a multilateral force authorized by the UN should intervene if politically possible. The Standing High Readiness Brigade, EU Rapid Response Force, or regional forces (NATO, ASEAN, ECOWAS) — should be authorized to act by the UN Security Council.

The UN General Assembly may authorize action under the Uniting for Peace Resolution G A Res. 330 (1950), which has been used 13 times for such armed intervention.

If the UN is paralyzed, regional alliances must act under Chapter VIII of the UN Charter. The international responsibility to protect transcends the narrow interests of individual nation states. If strong nations will not provide troops to intervene directly, they should provide the airlift, equipment, and financial means necessary for regional states to intervene.

Stage 10: Denial

Denial is the final stage that lasts throughout and always follows genocide. It is among the surest indicators of further genocidal massacres.

The perpetrators of genocide dig up the mass graves, burn the bodies, try to cover up the evidence, and intimidate the witnesses. They deny that they committed any crimes, and often blame what happened on the victims. Acts of genocide are disguised as counter-insurgency if there is an ongoing armed conflict or civil war.

Perpetrators block investigations of the crimes, and continue to govern until driven from power by force, when they flee into exile. There they remain with impunity, like Pol Pot or Idi Amin, unless they are captured and a tribunal is established to try them.

During and after genocide, lawyers, diplomats, and others who oppose forceful action often deny that these crimes meet the definition of genocide. They call them euphemisms like "ethnic cleansing" instead. They question whether intent to destroy a group can be proven, ignoring thousands of murders. They overlook deliberate imposition of conditions that destroy part of a group. They claim that only courts can determine whether there has been genocide, demanding "proof beyond a reasonable doubt," when prevention only requires action based on compelling evidence.

The best response to denial is punishment by an international tribunal or national courts. There the evidence can be heard and the perpetrators punished. Tribunals like the Yugoslav, Rwanda or Sierra Leone Tribunals, the tribunal to try the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, or the International Criminal Court may not deter the worst genocidal killers. But with the political will to arrest and prosecute them, some may be brought to justice. Local justice and truth commissions and public school education are also antidotes to denial. They may open ways to reconciliation and preventive education.

From Learning To Action

Operation Broken Silence is building a global movement to empower Sudanese genocide survivors in the war-torn periphery regions of Sudan, including teachers in Yida Refugee Camp. Teachers just like Chana.

The Endure Primary and Renewal Secondary Schools we sponsor in Yida are run entirely by Sudanese teachers. Your gift will help pay educator salaries, deliver school supplies and more.

If you can’t donate right now, we encourage you start a fundraising page and ask friends and family to give!

We are a 501(c)3 tax-exempt organization. Your donation is tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law.