News & Updates

Check out the latest from Sudan and our movement

The Genocide Convention

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide codified the crime of genocide into international law. It was adopted following the atrocities committed during the Second World War.

Photo: Delegates from countries that signed the UN Genocide Convention. United Nations.

This historical document provides a contextual background for understanding the issues Operation Broken Silence works on. It is part of our resource list for students, teachers, and the curious and was last updated January 2024. For more information about what's happening in Sudan and our work, please sign up for our email list.

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Genocide Convention) codified the crime of genocide into international law.

The Genocide Convention was the first human rights treaty adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations on December 9, 1948, following atrocities committed during the Second World War. Although the world still struggles today to fulfill the promise of “never again” when it comes to the crime of genocide, the Genocide Convention marked a crucial step toward the development of international human rights and international criminal law as we know it today. The text can be found below.

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

Approved and proposed for signature and ratification or accession by General Assembly resolution 260 A (III) of 9 December 1948 Entry into force: 12 January 1951, in accordance with article XIII

The Contracting Parties,

Having considered the declaration made by the General Assembly of the United Nations in its resolution 96 (I) dated 11 December 1946 that genocide is a crime under international law, contrary to the spirit and aims of the United Nations and condemned by the civilized world,

Recognizing that at all periods of history genocide has inflicted great losses on humanity, and

Being convinced that, in order to liberate mankind from such an odious scourge, international co-operation is required,

Hereby agree as hereinafter provided:

Article I

The Contracting Parties confirm that genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which they undertake to prevent and to punish.

Article II

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Article III

The following acts shall be punishable:

(a) Genocide;

(b) Conspiracy to commit genocide;

(c) Direct and public incitement to commit genocide;

(d) Attempt to commit genocide;

(e) Complicity in genocide.

Article IV

Persons committing genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in article III shall be punished, whether they are constitutionally responsible rulers, public officials or private individuals.

Article V

The Contracting Parties undertake to enact, in accordance with their respective Constitutions, the necessary legislation to give effect to the provisions of the present Convention, and, in particular, to provide effective penalties for persons guilty of genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in article III.

Article VI

Persons charged with genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in article III shall be tried by a competent tribunal of the State in the territory of which the act was committed, or by such international penal tribunal as may have jurisdiction with respect to those Contracting Parties which shall have accepted its jurisdiction.

Article VII

Genocide and the other acts enumerated in article III shall not be considered as political crimes for the purpose of extradition.

The Contracting Parties pledge themselves in such cases to grant extradition in accordance with their laws and treaties in force.

Article VIII

Any Contracting Party may call upon the competent organs of the United Nations to take such action under the Charter of the United Nations as they consider appropriate for the prevention and suppression of acts of genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in article III.

Article IX

Disputes between the Contracting Parties relating to the interpretation, application or fulfilment of the present Convention, including those relating to the responsibility of a State for genocide or for any of the other acts enumerated in article III, shall be submitted to the International Court of Justice at the request of any of the parties to the dispute.

Article X

The present Convention, of which the Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish texts are equally authentic, shall bear the date of 9 December 1948.

Article XI

The present Convention shall be open until 31 December 1949 for signature on behalf of any Member of the United Nations and of any non-member State to which an invitation to sign has been addressed by the General Assembly.

The present Convention shall be ratified, and the instruments of ratification shall be deposited with the Secretary-General of the United Nations.

After 1 January 1950, the present Convention may be acceded to on behalf of any Member of the United Nations and of any non-member State which has received an invitation as aforesaid.

Instruments of accession shall be deposited with the Secretary-General of the United Nations.

Article XII

Any Contracting Party may at any time, by notification addressed to the Secretary- General of the United Nations, extend the application of the present Convention to all or any of the territories for the conduct of whose foreign relations that Contracting Party is responsible.

Article XIII

On the day when the first twenty instruments of ratification or accession have been deposited, the Secretary-General shall draw up a procès-verbal and transmit a copy thereof to each Member of the United Nations and to each of the non-member States contemplated in article XI.

The present Convention shall come into force on the ninetieth day following the date of deposit of the twentieth instrument of ratification or accession.

Any ratification or accession effected subsequent to the latter date shall become effective on the ninetieth day following the deposit of the instrument of ratification or accession.

Article XIV

The present Convention shall remain in effect for a period of ten years as from the date of its coming into force.

It shall thereafter remain in force for successive periods of five years for such Contracting Parties as have not denounced it at least six months before the expiration of the current period.

Denunciation shall be effected by a written notification addressed to the Secretary- General of the United Nations.

Article XV

If, as a result of denunciations, the number of Parties to the present Convention should become less than sixteen, the Convention shall cease to be in force as from the date on which the last of these denunciations shall become effective.

Article XVI

A request for the revision of the present Convention may be made at any time by any Contracting Party by means of a notification in writing addressed to the Secretary- General.

The General Assembly shall decide upon the steps, if any, to be taken in respect of such request.

Article XVII

The Secretary-General of the United Nations shall notify all Members of the United Nations and the non-member States contemplated in article XI of the following:

(a) Signatures, ratifications and accessions received in accordance with article XI; (b) Notifications received in accordance with article XII;

(c) The date upon which the present Convention comes into force in accordance with article XIII;

(d) Denunciations received in accordance with article XIV;

(e) The abrogation of the Convention in accordance with article XV;

(f) Notifications received in accordance with article XVI.

Article XVIII

The original of the present Convention shall be deposited in the archives of the United Nations.

A certified copy of the Convention shall be transmitted to each Member of the United Nations and to each of the non-member States contemplated in article XI.

Article XIX

The present Convention shall be registered by the Secretary-General of the United Nations on the date of its coming into force.

From Learning To Action

Our free global event turns everyday runs, bike rides, and walks into lifesaving support. Every mile you put in and dollar you raise helps fund emergency aid, healthcare, and education programs led by Sudanese heroes. We also have an option where you can skip the exercise and just fundraise. Every dollar raised makes a difference.

We are a 501(c)3 tax-exempt organization. Your donation is tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law.

The Dangers of Genocide Denial

Genocide denial is the attempt to minimize or redefine the scale and severity of a genocide, and sometimes even deny a genocide is or was being committed.

Photo: A home in Sudan’s Nuba Mountains smolders after being bombed by a regime warplane. The Sudanese government has denied committing two genocides in the region. (Operation Broken Silence)

This is a brief article providing a contextual background for understanding the issues Operation Broken Silence works on. It is part of our resource list for students, teachers, and the curious and was last updated January 2023. For more information about what's happening in Sudan and our work, please sign up for our email list.

Genocide denial is the attempt to minimize or redefine the scale and severity of a genocide, and sometimes even deny a genocide is or was being committed. It is the final stage of The 10 Stages of Genocide, a processual model that aims to demonstrate how genocides are committed.

The goal of genocide denial is twofold: cast doubt on charges of genocide to protect perpetrators and silence survivors. Genocide denial is an extended process that requires significant resources. It often begins before crimes are being committed and continues decades after the killing ends.

Examples of Genocide Denial

Campaigns of genocide denial are multi-faceted and cover a variety of actions. These are some of the common aspects that can be found in most genocide denials:

Redefining The Killing - Perpetrators and their enablers will often try to replace charges and accusations of genocide with a variety of terms, such as claiming that the killings are a “counter-insurgency” or civilians “caught in the crossfire” of a civil war. Sometimes perpetrators will even express false public remorse that civilians have been killed, but also claim that they were killed inadvertently.

Arguing Down The Numbers Of Those Killed - Human rights monitors, journalists, and other investigative entities usually don’t have full access to genocide-afflicted areas, so estimates of the number of people killed are often provided to the public. Perpetrators will often try to minimize the number of people who have been killed in the targeted group, knowing that date which is 100% accurate is not available to the world. For example, throughout the Darfur genocide, the Sudanese government regularly claimed that only 10,000 people had died, while evidence-based, conservative estimates stated over 250,000 people had been killed.

Victim Blaming - Perpetrators will often blame the victims, making false accusations that the aggressor was attacked first and they responded in “self-defense.” The most egregious perpetrators will claim that the victims “deserved it,” dehumanizing them even further to drive more killing and the silencing of survivors.

Denying Ongoing Killing - Genocide denial often starts before extermination begins, with the perpetrators brushing off concerns and warnings that a genocide they are preparing is imminent. Campaigns of denial are often become more elaborate when the killing begins. In rare moments of intense international focus, perpetrators will often deny committing or having specific knowledge of individual massacres they are accused of participating in.

Blocking Human Rights Investigations - Perpetrators will often block human rights monitors, journalists, and other investigative persons from entering afflicted areas. They will claim that outsiders are not allowed in because security is poor or blame the victim group, which may have self-armed to defend themselves. This prevents experts, humanitarian relief, and security assistance from reaching the most at-risk people and keeps the world in the dark on the specifics of a genocide.

Destruction of Evidence - Fearing criminal prosecution or an armed intervention by outside military forces, perpetrators will often dig up mass graves, burn the bodies, and try to cover up evidence and intimidate any witnesses. Documents and photographic evidence are sought out and destroyed. Lower-level perpetrators who carried out the killing face-to-face may be targeted by their commanders as part of the cover-up.

The Dangers of Genocide Denial

Genocide is a widespread enterprise, often involving tens of thousands of perpetrators up and down chains of command. Campaigns of genocide denial are rarely, if ever, successful in the long run. There are simply too many individual perpetrators involved to cover up every detail and shred of evidence, as well as survivors who have documented their own experiences.

Regardless, genocide denial still poses grave risks to victim groups and survivors, nation-states in which genocide has been committed, and international security.

Victim Groups and Survivors - Genocide denial is often painful to victim groups and survivors, even to generations who live after the crimes were committed. It is not just a denial of truth and reality, but also denies them the ability to heal, rebuild, and ease generational trauma. Research also suggests that one of the single best predictors of a future genocide is denial of a past genocide coupled with impunity for its perpetrators.

As long as the perpetrator group is in power, genocide denial provides an avenue to continue the genocide and prevent survivors and victims from finding paths forward. Yet even if perpetrators are removed from power, there are often still individuals and groups who rise up to deny a genocide. For example, Holocaust denialism still exists today despite the fall of Nazi Germany and the genocide being well-documented by the Nazis themselves.

Nation-States - Countries in which genocide has been committed and is being denied often face an array of challenges and threats in the aftermath. Large refugee and internally-displaced persons camps, devastated communities, poverty, insecurity, and more are left in the wake of a genocide. Societies are fractured and people groups –including bystanders– have lost trust in their neighbors.

Even if the perpetrator group has fallen from power, new governments often struggle to provide security, reparations, and truth and reconciliation processes to the citizenry. In some cases, genocide denial can lead to survivors taking matters into their own hands and committing revenge killings, which can lead to more genocidal massacres of the victim group.

International Security - The crime of genocide provides cover for other international crimes, such as weapons, human, and drug trafficking, wildlife poaching, and valuable natural resources being seized to fund more killing. Perpetrator militias and combatants may cross international borders to attack fleeing victims or help nearby allies, spreading chaos and insecurity as they go.

For example, Sudanese regime militias have fought in others wars in Libya, Central African Republic, and Yemen. They also control lucrative gold mines, cross international borders to poach endangered wildlife, and have participated in human and weapons trafficking networks. Their destabilizing impact has been felt throughout central, northern, and eastern Africa, not just in Sudan.

From Learning To Action

Our free global event turns everyday runs, bike rides, and walks into lifesaving support. Every mile you put in and dollar you raise helps fund emergency aid, healthcare, and education programs led by Sudanese heroes. We also have an option where you can skip the exercise and just fundraise. Every dollar raised makes a difference.

Checks can be made payable to Operation Broken Silence and mailed to PO Box 770900 Memphis, TN 38177-0900. You can also donate stock or crypto. Operation Broken Silence a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Donations are tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law. Our EIN is 80-0671198.

What Are Mass Atrocity Crimes?

Mass atrocities refer to large-scale, systematic violence against civilian populations. Learn more.

This is a brief article providing a contextual background for understanding the issues Operation Broken Silence works on. It is part of our resource list for students, teachers, and the curious and was last updated January 2024. For more information about what's happening in Sudan and our work, please sign up for our email list.

Mass Atrocities & Mass Killing

The term mass atrocities refers to large-scale, systematic violence against civilian populations. The term mass killing is generally used to refer to the deliberate actions of armed groups — including but not limited to state security forces, rebel armies, and other militias — that result in the deaths of at least 1,000 noncombatant civilians targeted as part of a specific group over a 12-month period.

Neither term has a former legal definition. Both are frequently used as an overarching, collective way to speak about other definitions found in this article and to draw attention to larger-scale conflicts and incidents in which the lives of civilians are at grave risk.

Genocide

Genocide is an internationally recognized crime where acts are committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. These acts fall into five categories:

Killing members of the group

Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group

Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part

Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group

Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group

Genocide differs from other crimes because it must be motivated by a specific intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, racial, ethnical, or religious group. Some of the acts involved in genocide, such as killing or sexual violence, can also constitute war crimes and crimes against humanity; however, for these acts to constitute genocide, they must be committed with the intent to destroy.

Ethnic Cleansing

The term ethnic cleansing refers to the forced removal of an ethnic group from a specific geographic area. A United Nations Commission of Experts investigating mass atrocity crimes in the former Yugoslavia defined it as “rendering an area ethnically homogeneous by using force or intimidation to remove persons of given groups from the area.”

Similar to the terms mass atrocities and mass killing, it is important to note that ethnic cleansing is not recognized as a standalone crime under international law. The practice of ethnic cleansing may constitute genocide, crimes against humanity, or war crimes though.

Left: The aftermath of an attack in the village of Masteri in west Darfur on July 25, 2020 (Mustafa Younes via AP). Right: The aftermath of a village being bombed in the Nuba Mountains in 2012 (Operation Broken Silence).

Crimes Against Humanity

Crimes against humanity are defined in Article 7 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court as “any of the following acts when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack:

Murder;

Extermination;

Enslavement;

Deportation or forcible transfer of population;

Imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law;

Torture;

Rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilization, or any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity;

Persecution against any identifiable group or collectivity on political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious, gender as defined in paragraph 3, or other grounds that are universally recognized as impermissible under international law, in connection with any act referred to in this paragraph or any crime within the jurisdiction of the Court;

Enforced disappearance of persons;

The crime of apartheid;

Other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health.

In order for any of the above acts to constitute crimes against humanity, two elements must be met: the act committed against a civilian population (as opposed to soldiers or other non-civilian populations), and the act must be part of a widespread or systematic attack (not singular violations). Crimes against humanity are distinguished from “ordinary” crimes by being widespread or systematic, and by the targeting of civilians. Because crimes against humanity can be committed in the context of an armed conflict, it is possible for the same act to constitute both a crime against humanity and a war crime.

War Crimes

War crimes are defined in Article 8 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court as grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, namely, any of the following acts against persons or property protected under the provisions of the relevant Geneva Convention:

Wilful killing;

Torture or inhuman treatment, including biological experiments;

Wilfully causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or health;

Extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly;

Compelling a prisoner of war or other protected person to serve in the forces of a hostile Power;

Wilfully depriving a prisoner of war or other protected person of the rights of fair and regular trial;

Unlawful deportation or transfer or unlawful confinement;

Taking of hostages.

Article 8 continues to define additional crimes that occur in the context of international and internal armed conflicts, such as killing or wounding already-surrendered enemy combatants, pillaging, and more.

War crimes, by definition, can only be committed in the context of an armed conflict. These crimes involve grave breaches of the laws of war, committed against people or entities who are protected under those laws (such as civilians and their property) and/or the use of prohibited methods or means of warfare. The acts that can constitute war crimes range from willful killing to pillaging, sexual violence, and declaring that there will be “no mercy” in a military operation.

From Learning To Action

Our free global event turns everyday runs, bike rides, and walks into lifesaving support. Every mile you put in and dollar you raise helps fund emergency aid, healthcare, and education programs led by Sudanese heroes. We also have an option where you can skip the exercise and just fundraise. Every dollar raised makes a difference.

Checks can be made payable to Operation Broken Silence and mailed to PO Box 770900 Memphis, TN 38177-0900. You can also donate stock or crypto. Operation Broken Silence a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Donations are tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law. Our EIN is 80-0671198.

Darfur

The history of the geographic region known as Darfur stretches back centuries. This overview focuses on the time period after Sudan’s independence in 1956.

Photo: A group of women ride donkeys on their way to farm land near Um baru, North Darfur during the rainy season. Women, children and elder people often work in fields near displacement camps to avoid rapes and robberies. (Hamid Abdulsalam, UNAMID)

This historical overview provides a contextual background for understanding the issues Operation Broken Silence works on. It is part of our resource list for students, teachers, and the curious and was last updated January 2024. For more information about what's happening in Sudan and our work, please sign up for our email list.

Introduction

While the history of Darfur stretches back centuries, this overview focuses on the time period after Sudan’s independence in 1956. A chronological examination of the Darfur region in the contemporary era can be broken out into five main periods:

Pre-Modern & Colonial Background: 1200 BCE-1956 CE

Instability & Rising Tensions: 1956-1988

Rise of the Bashir Regime & Intercommunal Violence: 1989-2000

The Darfur Genocide (Part 1): 2001-2008

The Darfur Genocide (Part 2): 2009-2019

A summary of the post-2019 situation in Darfur is provided at the end as well.

Map: Location of Darfur. (Operation Broken Silence)

Photo: “Young Girl from Darfur” by Pierre Trémaux (circa 1855) is thought to be one of the first photographs highlighting Darfur.

Pre-Modern & Colonial Background: 1200 BCE-1956 CE

Darfur has an ancient history that offers few details, with the first known peoples belonging to several distinct ethnicities and related languages of the Daju people. Ancient Egyptian texts suggest an established Daju kingdom existed in the Marrah Mountains (present day central Darfur) as early as the 12th century BCE.

Although the geographic area known as Darfur has been inhabited for millennia, little direct documentation of life here is mentioned before 1600 CE, when more detailed information becomes available as the Fur people rose to power in Darfur. This undocumented history likely has roots in just how isolated the region has often been. Even today, archeological efforts in Darfur have been extremely minimal when compared to other parts of the world —despite potential excavation sites being known— leaving much of the region’s ancient and pre-modern historical understanding to tradition.

It is important to note that this isolation does not remove the historical causes of recent trouble in the region. Attacks on Darfur’s rich, diverse cultural tapestry by national military regimes in Khartoum, including the crime of genocide, have entrenched real historical grievances in countless communities.

Depending on who you ask, Darfur is home to between 36-80 tribes and ethnic groups that fall within the broader categories of African and Arab. The word Darfur refers to the region’s largest African ethnic group: the Fur. The first known historical mention of the Fur was in a 1664 account by Johann Michael Vansleb, a German theologian and traveler who was visiting Egypt. The Arabic word dar can be translated literally as home or house. Darfur then can be translated as home of the Fur.

Photo: Sudan's flag raised at the independence ceremony in January 1, 1956 by Prime Minister Ismail al-Aazhari and opposition leader Mohamed Ahmed al-Mahjoub. (Sudan Films Unit, Wikimedia Commons)

The vast majority of Darfuris are Muslim. A small Christian minority resides in Darfur, but estimates on the size of this community vary as many churches have met secretly in homes due to government persecution.

In 1899, the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium administrated Sudan as a colony. The joint British and Egyptian colonial government invested heavily in the Arab-dominated central and eastern parts of the country. Like other periphery regions of Sudan, Darfur was largely marginalized and ignored. The region was officially integrated into Sudan under colonial rule during World War I.

Shortly after Sudan’s independence on January 1, 1956, African Darfuri civil society groups advocated for a larger role in the country. Like many of Sudan’s ethnically African minorities, these groups were increasingly ignored by Arab-dominated governments in Khartoum. This led to mistrust between the country's powerful center and large swaths of Darfur and growing outside pressures on the region, both of which helped to set the stage for armed conflict that continues today.

Instability & Rising Tensions: 1956-1988

Map: Darfur’s porous borders have exacerbated local issues for decades, bringing weapons, armed groups, and Arab settlers into the region. (Operation Broken Silence)

Following Sudan's independence, African tribal groups in Darfur witnessed growing tension with Arab-dominated governments in Khartoum. The violent ideologies of Arabization and Islamization gained stronger traction in Sudan’s center. From the 1960s forward, Arab tribal groups in Darfur expanded their influence both within and outside of Darfur’s borders. Arab tribesman from across the Sahel also began settling in Darfur, often times near or on land belonging to ethnically African groups like the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa.

Changing regional dynamics between Sudan, Libya, and Chad pressed in on the region during these years. Darfur became a safe haven for Arab rebel groups fighting in Chad, with the governments of Sudan and Libya directly engaged on and off again in that conflict.

The situation in Darfur began to destabilize more rapidly in the 1980s. A horrific famine gripped the region and the Sudanese government was increasingly supporting Arab tribes in Darfur, who were seen as allies with the country's Arab political power base in Khartoum.

By the late 1980s, Darfur was awash in weapons after years of various government and rebel activities involving Sudan, Chad, Libya, and the Central African Republic and settlers from other countries across the Sahel.

Rise of the Bashir Regime & Intercommunal Violence: 1989-2000

In 1989, Colonel Omar al-Bashir and the National Islamic Front seized power in a military coup. Bashir took the titles of president, chief of state, prime minister, and chief of the armed forces. Wielding a Koran and an AK-47 rifle in Khartoum, Bashir declared to soldiers that he was going to reengineer the country into one dominated by an ethnic Arab elite and ruled by oppressive Islamic law.

Between 1989-1991, Bashir consolidated control over the government by banning trade unions, political parties, and other non-religious institutions. Over 70,000 members of the army, police, and civil administration were purged. The regime began to recruit, train, and arm Arab tribal militias in Darfur. This highlights a step in the 10 Stages of Genocide.

In 1991, Sudan's civil war in southern Sudan briefly spilled into Darfur. An armed southern rebel unit entered Darfur in an attempt to spread resistance to the Bashir regime. The southern rebel force was defeated by the Sudanese army and their Arab militia allies. African Darfuri communities seen as sympathetic to the plight of their southern neighbors were attacked and destroyed, a grim warning of what was to come a decade later.

In 1994, the Bashir regime divided Darfur into three federal states to hinder Darfuri African tribes, predominantly the Fur, from effectively mobilizing in support of ideas and policies that countered the regime.

As the century came to a close, war between large swaths of Darfur and the Bashir regime was becoming inevitable. Arab militias armed by the regime attacked Fur and Masalit communities at an alarming rate, causing the Fur and Masalit to self-arm. Clashes between both sides increased in scope and severity due to a number of decades-old issues including Arab racism against Africans, land use, basic rights, and access to markets.

Masalit fighters briefly gained the upper hand in 1999 by killing several Arab militia leaders who had led attacks on their communities. The Bashir regime responded by sending in the Sudanese army to arrest, imprison, and torture Masalit intellectuals and leaders and destroy Masalit villages.

In 2000, the brewing crisis reached the tipping point. A group of future Darfuri rebel leaders published The Black Book, a dissident piece of literature outlining Arab and regime abuses against African Darfuris. The Bashir regime failed to suppress The Black Book and talk of armed rebellion spread across Darfur.

Photo: A member of the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), one of the main armed rebel groups in Darfur that formed after years of regime oppression. (Hamid Abdulsalam, UNAMID)

The Darfur Genocide (Part 1): 2001-2008

As the world entered a new millennium, Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa leaders organized their fighters into rebel groups. The largest two were the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) and Justice & Equality Movement (JEM).

From 2001-2002, African Darfuri rebels attacked small regime army outposts, police stations, and Arab militias. Verbal threats from Bashir and regime counteroffensives failed to quell the rebellion. With the civil war in southern Sudan and genocide in the Nuba Mountains ongoing, the Sudanese army was ill-prepared to fight in Darfur. Regime soldiers were also facing a new kind of war in Darfur: semi-desert warfare, which was highlighted by fast-moving vehicles and hit-and-run tactics.

The Bashir regime began bombing known rebel bases and unarmed villages in the central Marrah Mountains, but failed to slow the speed at which the rebellion was catching on.

Early on the morning of April 25, 2003, organized SLA and JEM rebels entered El Father, the capital of North Darfur, home to a critical regime military base. The following four hour-long rebel assault saw seven Antonov bombers and helicopters destroyed and over 100 regime troops and pilots killed or captured, including the base commander.

The success of the rebel raid on such a critical regime military base was unprecedented. The Bashir regime would no longer ignore growing armed resistance to their iron-fisted rule.

Map: The Marrah Mountains have been a rebel-stronghold in Darfur for years. Regime forces have been unable to take control of the area, so government warplanes and artillery units have frequently targeted villages here. (Operation Broken Silence)

As government warplanes intensified bombings of unarmed African communities and rebel positions, the Bashir regime started to mass recruit, arm, and train large numbers of militiamen from several Arab tribes. The militias would become known as the Janjaweed, or devil on horseback. They would become the backbone of the brutal killing machine that was about to be unleashed against African tribes who formed the core of armed opposition groups - primarily the Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit.

Initial Janjaweed recruits to the government's war and genocide in 2003 came mainly from two Arab groups - herders from North Darfur and immigrants/mercenaries from Chad. While some Arab communities remained neutral, specifically those who owned land, Sudanese government promises of war loot and new land encouraged thousands of young Arab men to join the Janjaweed.

By the end of 2003, large numbers of Janjaweed units mounted on horseback had unleashed a scorched-earth campaign against Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit communities across Darfur. They destroyed everything that made life possible, including clean water wells, orchards, markets, and mosques.

The Janjaweed’s campaign inflicted death, displacement, and destruction on a shocking scale. Tens of thousands of civilians were killed and entire villages were razed to ground in the first few years of the genocide. Another two and a half million were driven into displacement camps, where small contingents of African Union peacekeeping troops —who had deployed into Darfur in 2006– had neither the mandate nor the resources to protect terrified Darfuris. More than 200,000 refugees fled across the border into Chad.

In 2004, senior U.S. government officials began describing the crisis as a genocide committed by the Bashir regime against African Darfuri groups.

Photo: A rebel fighter examines a burnt animal in Tukumare, north Darfur. The village was abandoned after clashes between the Sudanese army/Janjaweed and Darfuri rebels. (Albert Gonzalez Farran, UNAMID)

The genocide turned the tide of the war in favor of the regime. Darfuri rebel groups fractured underneath the Janjaweed’s widespread crimes and regime manipulation. The SLA and JEM’s guerrilla tactics remained an effective strategy; however, it did little to slow down the Janjaweed, who often times responded to rebel attacks by massacring entire Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit villages.

In March 2005, the United Nations Security Council referred the human rights catastrophe in Darfur to the International Criminal Court.

The Bashir regime and a faction of the SLA signed the Darfur Peace Agreement in May 2006 after seven rounds of African Union-led negotiations. JEM and another SLA faction refused to sign, saying compensation guarentees and the disarmament of the Janjaweed needed to be prioritized in any agreement.

A handful of other individual rebel commanders and splinter groups signed Declarations of Commitment to the agreement. Some were then armed by the regime and turned against their former allies, especially in North Darfur. The regime’s divide-and-conquer strategy had an expanding number of rebel groups fighting each other and the Janjaweed. Meanwhile, daily aerial bombings of communities continued paving the way for Janjaweed units to pillage, rape, and kill on a horrifying scale.

In mid-2006, the Bashir regime ordered the military back to the frontlines in a new offensive against rebel groups who had not signed the Darfur Peace Agreement. For a brief time, many Darfuri rebel groups put aside their differences to fend off the army’s renewed invasion of Darfur. This short-lived alliance between over a dozen Darfuri rebel factions was effective in helping the armed groups survive, but the army’s offensive proved disastrous for ordinary Darfuri communities.

Photo: Ahmed Haroun, the former Sudanese junior interior minister responsible for the western Darfur region was named as a suspect for war crimes in Darfur by the International Criminal Court's prosecutor, Feb. 27, 2007, gives a press conference at the presidential palace in Khartoum, Sudan in this 2006 file photo. Harun and a janjaweed militia leader, Ali Mohammed Ali Abd-al-Rahman, also known as Ali Kushayb, were suspected of a total of 51 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity, according to prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo. (AP Photo/Abd Raouf)

By September 2006, Darfur had become one of the greatest humanitarian catastrophes in the world. Hundreds of thousands of innocent people were out of reach of humanitarian aid due to expanding Janjaweed violence. With accusations of a government-backed genocide on the rise, the United Nations began working with the African Union to replace and enhance the weak international presence in Darfur.

In 2007, the International Criminal Court issued global arrest warrants for Ahmed Haroun, a senior regime official, and Ali Kushayb, a high-ranking Janjaweed leader, on dozens of counts of war crimes. In 2008, the court would also issue an arrest warrant for dictator Omar al-Bashir.

Meanwhile, the small African Union peacekeeping force in Darfur could barely protect itself, much less millions of terrified Darfuris seeking protection from the Janjaweed. By May of 2007, the peacekeeping force was on the verge of collapse due to a lack of resources and a hostile environment. The force would be transitioned to a stronger, United Nations-led command in 2008 called the United Nations - African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID). Thousands of international peacekeeping reinforcements would soon arrive in Darfur.

As Darfur continued to burn, the Bashir regime began resettling Arab tribes into areas of Darfur that had been "cleansed" of the African Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit tribes. This highlights another step in the 10 Stages of Genocide.

Photo: A woman rides a donkey while UNAMID troops from Tanzania conduct an armed patrol in South Darfur. (Albert Gonzalez Farran, UNAMID)

The Darfur Genocide (Part 2): 2009-2019

By 2009, it was clear that international efforts to save lives in Darfur were facing serious challenges from the Bashir regime. UNAMID peacekeeping patrols were being blocked by regime soldiers and Janjaweed militias. Mass violence had eased, but peacekeepers could often not access areas of Darfur where conflict remained ongoing. The Janjaweed and other regime-armed Arab groups continued to settle on land that the African Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit tribes had been driven off of.

Things only got worse in March of 2009, when the Bashir regime expelled international aid organizations from Darfur. This left hundreds of thousands of the most vulnerable people with little to no international support.

Under intense pressure from the Bashir regime, United Nations peacekeeping officials took a series of devastating steps that undermined the integrity of UNAMID’s mission. Rather than challenging ongoing regime war crimes being reported by their peacekeepers, UN officials began covering them up as early as 2009. Whistleblowers from within the peacekeeping mission emerged to decry these actions. UN officials took no concrete steps to address them.

It’s also during this period that Darfur began to fall out of the international spotlight. South Sudan’s upcoming independence and new crises coming out of the Arab Spring pulled the world’s attention away. UNAMID peacekeepers continued to struggle to provide security to all of Darfur’s persecuted African tribal groups; however, the mere presence of the peacekeeping force kept much of the large-scale fighting and attacks on communities at bay in areas that had a UNAMID presence.

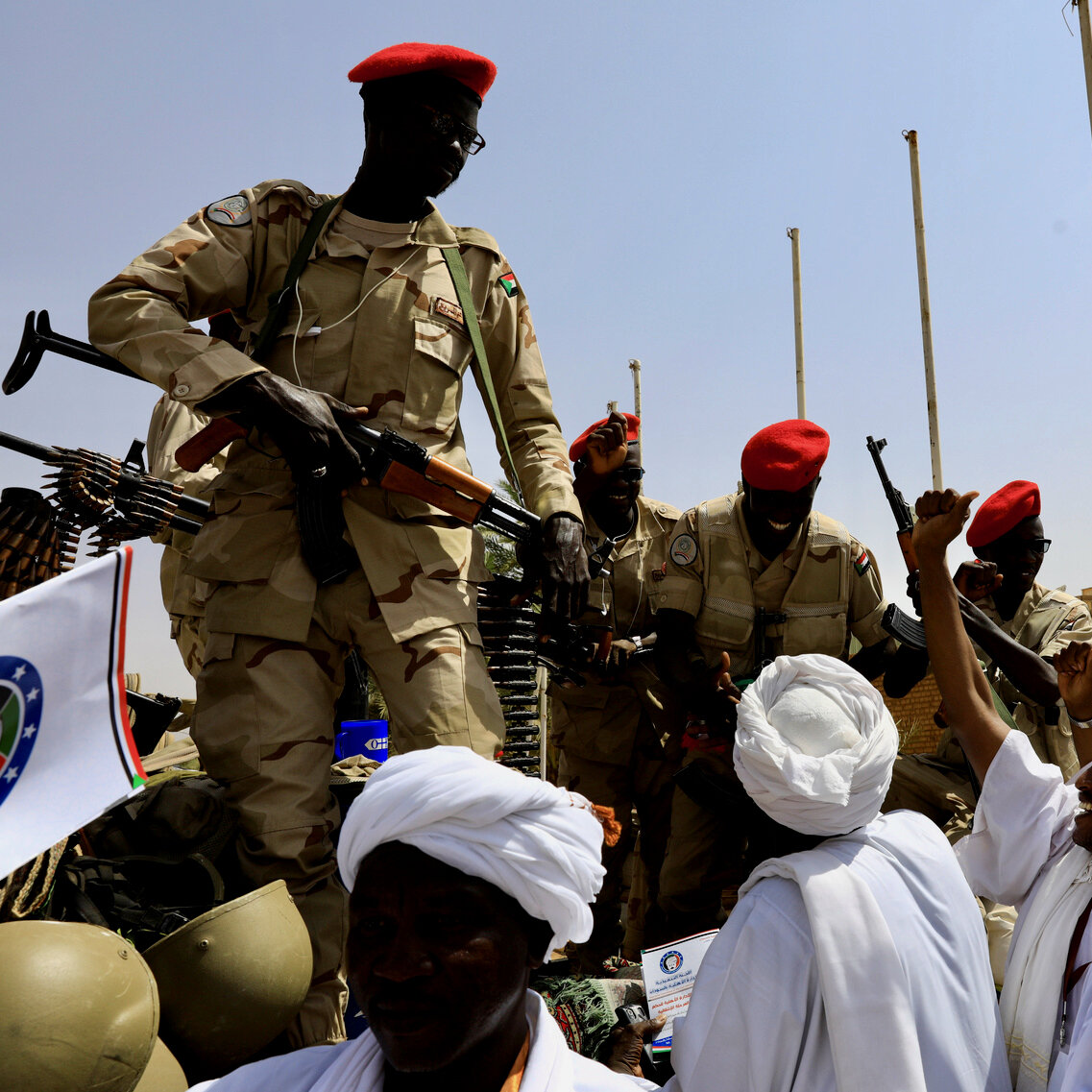

Photo: Rapid Support Forces paramilitaries dismount from their vehicle in Khartoum. (Umit Bektas/Adobe)

In 2013, the regime rebranded the Janjaweed as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and began outfitting the force with better equipment. Over the next few years, the RSF grew in size and strength, both by direct support from the regime and by using stolen land to mine gold, herd livestock, and more.

A grim warning of the RSF’s growing strength came in 2014, when the group launched a devastating assault on the rebel stronghold ofJebel Marra in central Darfur. While the brazen offensive failed to dislodge the rebels, the RSF forcibly displaced nearly 500,000 people in less than a month. The RSF’s new arsenal was on full display as well. Horses had been traded for modified SUVs with mounted machine guns. AK47s were supplemented with artillery, rocket-propelled grenades, and anti-aircraft guns.

Most concerning though was the increased international presence in the rank and file of the RSF. Survivors of RSF attacks noted that some of the paramilitaries were not Sudanese, but had come from neighboring Chad and Central African Republic. Islamist fighters from as far away as Mali had also entered the RSF’s ranks.

Over the next several years as the RSF grew in size, the paramilitary force spread to other hot spots in Sudan and beyond. RSF troops have committed mass war crimes in the southern Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile regions and have also popped up in major cities across Sudan. RSF units have also been implicated in illegal activity and war crimes in eastern Chad, the Central African Republic, and Yemen. The primary driver of on-the-ground violence in Darfur was now touching more and more aspects of daily life across Sudan.

Darfur Today (2019- Present)

In 2019, a civilian revolution swept across Sudan, leading to dictator Omar al-Bashir being overthrown by his own generals in April of that year. Following a horrific massacre by the RSF of peaceful protesters in Khartoum in June, renewed protests surged across Sudan and forced the regime to the negotiating table. A transitional government that was supposed to move the country toward free elections, democracy, and protection of basic human rights was implemented.

The transitional government was overthrown by surviving regime forces in October 2021. Leading the coup were the Sudanese army and RSF, two uneasy allies whose generals never saw eye-to-eye. Commanders in both organizations desired to see themselves as Sudan’s new ruling junta, with other armed regime groups beneath them.

From the time of the coup to early 2023, conditions in Sudan deteriorated on almost fronts. Inflation surged, peaceful protests resumed, humanitarian needs spread, and the web of oppression that transitional civilian leaders had been lifting was reinforced.

The RSF used this time to double down on becoming a self-sustaining force in Sudan, with Darfur as their stronghold. RSF generals fully secured their own weapons supply lines, launched international diplomatic efforts, entrenched themselves further in Darfur’s gold-mining sector, and began recruiting more fighters, both within Sudan and from other countries across the Sahel region. These actions almost always came at the expense of ordinary Sudanese, especially ethnically African Darfuris- who faced increasing attacks by RSF soldiers and dwindling economic opportunities.

Photo: A “Darfur Women Talking Peace” event at Al Salam displaced persons camp in El Fasher, North Darfur. Locally-led efforts like these to solve ongoing issues in Darfur continue to be blunted by RSF brutality. (Mohamad Almahady, UNAMID)

It also deteriorated the RSF’s tenuous relationship with the more dominant army, to the point of collapse. With long-promised progress on deeply-rooted fractures in Darfur elusive, evidence began to emerge as early as 2021 that Darfur was hurtling toward a new crisis.

The new war came on April 15, 2023. The RSF launched multiple attacks on army bases across Darfur and other regions of Sudan and attempted to seize government buildings in Khartoum. The lightening strike failed to knock the army out of power, with army units across the country putting up stiff resistance and bombing civilian areas RSF units attacked from. Both sides have engaged in large-scale war crimes, with the RSF using the fog of war to double down on their genocide of ethnic African minorities in Darfur.

While virtually every corner of Darfur has been negatively impacted by RSF violence, West Darfur especially has faced the brunt of the paramilitary force’s racism and brutality. Widespread genocidal massacres of the Masalit people group by the RSF and their local Arab allies abound. Tribal leaders and survivors of a two month-long massacre of the Masalit people in the city of El Geneina reported in June 2023 that over 10,000 of their people were killed in the city. Satellite imagery has confirmed entire neighborhoods and villages in West Darfur have been burned to the ground.

By the end of October 2023, most of Darfur had fallen under the control of the RSF. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of lives are in immediate danger. The crimes that began in Darfur over two decades ago are now being visited on much of Sudan, and the RSF is destroying the very government that created it.

The RSF and Darfur genocide highlight the interlinked issues of violence and silence across the country. The wars and attempted genocides in the Nuba Mountains, which the RSF has also participated in, highlight the structural issues of violence perpetuated by the regime. Due to the isolated location of both Darfur and the Nuba Mountains, violence and humanitarian blockades against ethnic minorities continue, and a lack of sustained media attention has kept the crises in Sudan from receiving the international attention they deserve.

The army-RSF war continues today and Darfur’s ethnic minorities are under siege. For more up to date information on the situation in Darfur and across Sudan, please visit our blog and sign up for our email list.

From Learning To Action

Our free global event turns everyday runs, bike rides, and walks into lifesaving support. Every mile you put in and dollar you raise helps fund emergency aid, healthcare, and education programs led by Sudanese heroes. We also have an option where you can skip the exercise and just fundraise. Every dollar raised makes a difference.

Checks can be made payable to Operation Broken Silence and mailed to PO Box 770900 Memphis, TN 38177-0900. You can also donate stock or crypto. Operation Broken Silence a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Donations are tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law. Our EIN is 80-0671198.

Yida Refugee Camp

The historical overview of a critical Sudanese refugee camp stretches back to the year 2011.

Photo: A young boy rides his family’s donkey toward the market in Yida Refugee Camp. (Operation Broken Silence)

This historical overview provides a contextual background for understanding the issues Operation Broken Silence works on. It is part of our resource list for students, teachers, and the curious and was last updated January 2024. For more information about what's happening in Sudan and our work, please sign up for our email list.

Introduction

Yida Refugee Camp in northern South Sudan came into existence in 2011, when the second war and attempted genocide in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan began. We encourage you to read our historical background piece on the Nuba Mountains before continuing here.

A chronological examination of Yida can be broken out into three main periods:

Pre-Existence To Founding : 2010-2011

Camp Growth & Humanitarian Challenges: 2011-2014

International Tension, Stability, & Population Decline: 2015-2019

Since Operation Broken Silence’s primary Sudanese partners work in the Nuba Mountains and Yida Refugee Camp, a summary of the current situation is provided at the end as well.

Map: Location of Yida Refugee Camp. (Operation Broken Silence)

Photo: A girl who survived an aerial bombing in the Nuba Mountains. Her mother brought them to Yida Refugee Camp in 2015. (Operation Broken Silence)

Pre-Existence To Founding: 1992-2011

The history of Yida Refugee Camp in northern South Sudan is intricately connected to the Nuba Mountains just across the border in Sudan. Yida sits roughly 17 miles away from the international border dividing the two countries. This demarcation is illustrative of the historical religious and ethnic grievances the Nuba Mountains and South Sudan have suffered underneath national military regimes in Khartoum.

The locality was depopulated of its native African tribal populations in the 1990s during the Second Sudanese Civil War. The Nuba Mountains of Sudan north of the area now known as Yida are inhabited by roughly 100 African tribes who have been referred to collectively as Nuba for centuries. Estimations vary wildly; however, it is generally thought that roughly 45% of the Nuba people are Christian, making the mountains home to the largest community of Christians in Sudan. Other religious affiliations include 45% of the population identifying as Muslim, with the remaining 10% following local tribal regions or identifying with no religion at all.

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, the Bashir regime of Sudan attempted to Islamize and Arabize the Nuba Mountains through war and genocide. This caused high levels of death and destruction on Nuba communities but ultimately strengthened the Nuba identity and armed resistance to the Bashir regime. The situation in the Nuba Mountains stabilized from 2003-2009 as the peace agreement that ended the Second Sudanese Civil War came into effect.

Some people resettled the area now known as Yida after the war ended in 2005, but it remained only sparsely inhabited by South Sudanese throughout the 2000s. By 2010, the area’s largest community was a small Dinka farming village of roughly 400 people. During the rainy season, the landscape transforms from being visually semi-arid into a lush, green wetland.

As southern Sudan prepared for an independence referendum in 2010, several soon-to-be international border areas between Sudan and southern Sudan witnessed rising tensions. The area that would become Yida Refugee Camp remained relatively quiet as it was shielded to north by the Sudan People's Liberation Army/Movement-North (SPLM-N) in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan and southern Sudan’s own military.

That began to change in 2011. From January-May, the Bashir regime of Sudan escalated militia attacks on isolated frontline communities in the Nuba Mountains. With southern Sudan on the verge becoming an independent country, it was clear that a new war was coming to the Nuba Mountains.

The return to war came early on the morning of June 6, 2011. Regime forces invaded the state capital of Kadugli and began massacring Nuba civilians. Survivors witnessed army soldiers and regime intelligence agents dragging Nuba people from their homes and executing them in the streets. Additional agents hunted through the city for Nuba leaders and intellectuals to kill, a step of the 10 Stages of Genocide.

Over a three-day period, the Bashir regime oversaw the systematic mass killing of thousands of Nuba civilians in Kadugli and began a widespread aerial bombing campaign on communities across the Nuba Mountains. Large numbers of Sudanese army forces and regime paramilitaries began to advance on the outskirts of the Nuba Mountains. Heavy fighting broke out across the frontlines. Nuba civilians fled for the safety of mountains or toward the South Sudan border.

Most of the initial refugees who arrived in Yida were survivors of the Kadugli massacre. They brought with them firsthand accounts of the killings. Along the way they had no sustainable food sources or clean water. The small farming village welcomed the new arrivals, offering food and land for them to farm. Yida Refugee Camp was born.

Rapid Camp Growth & Humanitarian/Security Challenges: 2011-2014

The ebb and flow of Nuba refugees into Yida since the outbreak of the war has matched the severity of armed conflict in the Nuba Mountains. During particularly intense stretches of regime aerial bombings and ground offenses, the population of Yida Refugee Camp has swelled. The first three years of the war witnessed major assaults on frontline communities and widespread aerial bombing against schools, markets, and places of worship. Yida Refugee Camp grew rapidly as a result, even with the critical road from the Nuba Mountains to Yida in South Sudan under constant threat by regime forces.

Over 30,000 refugees fled into Yida during the first year of the war. The regime responded by sending a warplane across the border to bomb the fledgling refugee camp in November 2011. This war crime caused considerable international outcry, making the regime decide not to launch such a brazen cross border attack again.

By July 2012, local aid workers were reporting over 600 new arrivals a day and growing humanitarian needs. Children were showing up malnourished and parents reported having to scavenge for leaves, roots, and tree sap to eat to sustain their journey to Yida. The World Food Program quickly scaled an emergency food distribution program to 21,000 people, but struggled to keep up with the growing population.

Three months later in October, Yida had more than doubled in size to roughly 65,000 people, with over 1,000 new arrivals flowing in on peak days. Driving the influx were Sudanese government warplanes, which had increased the frequency of bombing runs and begun using cluster munitions on Nuba villages.

As humanitarian conditions worsened in the camp, crime and basic security began to deteriorate as well. With no signs of a ceasefire or peace agreement on the horizon and humanitarian support lacking, community leaders in Yida Refugee Camp and local South Sudanese government officials began to push for more structure and services to address basic needs. A South Sudanese police force entered the camp and arrangements were made for refugees to begin farming the areas around Yida. An on again-off again effort to collect and remove small arms from the camp also picked up pace.

By January 2013, Yida’s population had swelled to over 70,000 people and little progress had been made on the camp’s humanitarian and security challenges. Relationships with nearby South Sudanese Dinka villages had also deteriorated. Local South Sudanese accused the Nuba refugees of harvesting their resources –including fish, wood, honey, and tall grass— to turn a profit at the growing market in Yida Refugee Camp. The Nuba refugees reported being robbed by members of nearby villages and being forced to pay taxes without any sort of documentation provided.

These tensions exploded into violence in March 2013. South Sudanese police and a Nuba militia —primarily made up of members from the Angolo tribe in Nuba— opened fire on each other. Armed Dinka militias entered parts of Yida and began looting homes and shops with police participation. More than 7,000 Nuba refugees fled north to the town of Jau, which sits on the Sudan-South Sudan border. The violence was finally quelled when a heavily-armed South Sudanese army force entered the camp to restore order.

The violence forced refugee leaders, local South Sudanese officials, and humanitarian organizations to focus on permanently improving conditions in the camp, even as the United Nations moved forward with opening additional camps in less secure areas. Throughout 2014 and over the next few years, more clean water wells would be dug, shelter supplies and food provided, schools opened, and limited medical services launched. A major effort to reduce the proliferation of weapons in the camp took on a more concrete form as well, leading to a reduction of Nuba militias and soldiers and more lightly armed South Sudanese police units.

In January 2014, regime forces launched a major offensive to capture the critical route connecting the Nuba Mountains to Yida Refugee Camp. After briefly losing control of a handful of key towns, the Nuba SPLM-N managed to defeat the attack and drive regime forces out of the area, permanently securing the road for refugees and trade flows in the area.

Photo: A Nuba woman waits for water to boil at her boon and tea shop in Yida’s market. (Operation Broken Silence)

Cultural Sustainment, International Tension, & Population Decline: 2015-2019

By 2015, Yida Refugee Camp had grown to be the largest Nuba community despite being outside of the mountains and in another country. The camp’s sheer size and improving humanitarian and security conditions made it a cultural and trading hub of the Nuba people.

The camp’s residential landscape was increasingly dotted with boon shops —a traditional Nuba coffee infused with ginger, cardamom and cinnamon— tea stalls, churches, schools, and community gathering and laundry sites. Community leaders created a process to handle local disputes peacefully. Nuba wrestling matches —a famous, historic sport in the mountains— brought in crowds to watch. Barbed wire that had been put up to help secure the camp’s perimeter was taken down and repurposed as clotheslines.

Yida’s expanding market and improved farming access also allowed for refugees to improve their own humanitarian conditions, as well as become a trading hub between the Nuba Mountains and South Sudan and nearby local communities. The camp was beginning to look more like a permanent city and economic engine in the region. Nuba teachers at most schools in the camp were underpaid and not well-resourced, but more and more children —one of the largest demographics in Yida— had access to a classroom, sometimes for the first time ever.

Challenges in Yida persisted despite improving conditions. In 2016, three churches were burned to the ground. International groups focused on Christian persecution reported that agents sent by the Sudanese government were responsible, but one of the church’s pastors informed Operation Broken Silence that they had no evidence of that being the reason. The congregations chose to forgive the perpetrators and rebuild.

Most notably, the relationship between the refugee community and United Nations (UN) became a source of growing anxiety in 2016. The UN had long referred to Yida as a “temporary” settlement and as the agency opened other less secure camps in South Sudan had begun calling Yida a “transit” area.

The reasoning provided for the UN’s growing discomfort with Yida has left much to be desired. Over the years, UN workers have claimed that the camp is too close to the border, plagued by armed actors, and that overpopulation was occurring. Nuba refugee leaders have asked for evidence of the latter two and partnership time and time again and received less and less in response.

Photo: Torched logs from one of the churches burned down in Yida. The rebuilt church sits in the background. (Operation Broken Silence)

The solutions offered by the UN fell even further short than the arguments. Efforts to replace Yida with other camps over the years have seen mostly negative results. A new UN camp called Nyeli flooded so frequently it had to be closed. While Yida is less than the 50-kilometers minimum distance from the border set by UN guidelines, the new UN camp Ajuong Thok did not meet the UN’s distance guidelines either. To make matters worse, the camp is near a section of the border that has historically been controlled by Sudanese regime forces, and residents felt it wasn’t safe to leave the camp after being threatened by local communities. Ajuong Thok was also nearing capacity by mid-2016 when the UN intensified efforts to close Yida, and another camp at Pamir wasn’t even built before the UN tried to move Nuba refugees there.

Many Yida residents thus refused to leave for new UN camps, even as the UN slowly reduced humanitarian operations from 2016 onward. However, Yida’s population began to decline in 2017 after the first ceasefire in the Nuba Mountains was signed. With the end of regime aerial bombing and major ground offensives, as well as slowly deteriorating humanitarian conditions in Yida, families began returning to their villages in the Nuba Mountains to rebuild.

Photo: A mother checks on her baby while cooking outdoors in Yida. (Operation Broken Silence)

Yida Refugee Camp Today (2019-Present)

In 2019, a civilian revolution swept across Sudan, leading to dictator Omar al-Bashir being overthrown by his own generals in April of that year. Following a horrific massacre of peaceful protesters in Khartoum in June, renewed protests surged across Sudan and forced the regime to the negotiating table. A transitional government that was supposed to move the country toward free elections, democracy, and protection of basic human rights was implemented.

The transitional government was overthrown by surviving regime forces in October 2021. Leading the coup were the Sudanese army and paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), two uneasy allies whose generals never saw eye-to-eye. Military leaders in both organizations desired to see themselves as Sudan’s new ruling junta, with other armed regime groups beneath them.

From the time of the coup to early 2023, conditions in Sudan deteriorated on almost fronts. Inflation surged, peaceful protests resumed, humanitarian needs spread, and the web of oppression that transitional civilian leaders had been lifting was reinforced.

The RSF used this time to double down on becoming a self-sustaining force in Sudan. RSF generals fully secured their own weapons supply lines, launched international diplomatic efforts, entrenched themselves further in Sudan’s gold-mining sector, and began recruiting more fighters, both within Sudan and from other countries across the Sahel region. These actions almost always came at the expense of ordinary Sudanese, who faced increasing attacks by RSF soldiers and dwindling economic opportunities.

Photo: A Nuba woman walks home from a clean water well in Yida. The well she used has since fallen into disrepair and closed. (Operation Broken Silence)

It also deteriorated the RSF’s tenuous relationship with the more dominant army, to the point of collapse. With a long-promised peace agreement elusive and coming fracturing of the regime all but sure, Nuba leaders had begun preparing for a new war shortly after the October 2021 coup. Meanwhile, in Yida Refugee Camp, clean water sites had begun falling into disrepair and schools struggled to gain access to basic supplies.

The new war came on April 15, 2023. The RSF launched multiple attacks on army bases across Sudan and attempted to seize government buildings in Khartoum. The lightening strike failed to knock the army out of power, with army units across the country putting up stiff resistance and bombing civilian areas RSF units attacked from. Both sides have engaged in large-scale war crimes, with the RSF using the fog of war to double down on their genocide of ethnic African minorities in Darfur.

At first, the Nuba Mountains were seen as a safe haven, with roughly 200,000 people from Khartoum and other areas fleeing into Nuba SPLM-N controlled areas and even into Yida Refugee Camp.

Fighting reached the western Nuba Mountains in June 2023. Small skirmishes between the army and SPLM-N devolved into major fighting around Kadugli and spread north to Dilling. The RSF entered the fray as well, attacking army forces from the west and north. While some Nuba communities near the frontlines have been forced to evacuate and prices of basic goods have soared, life goes on as usual in much of the rest of the Nuba Mountains and Yida Refugee Camp. There has been no widespread aerial bombings of villages as in previous wars, but the situation remains tense. It is believed that if the RSF makes serious gains in the region, more frontline communities will be at-risk, which would likely lead to new refugees entering Yida once more.

The army-RSF war continues today, as does fighting on the western frontlines of the Nuba Mountains. For more up to date information on the situation in the Nuba Mountains, Yida Refugee Camp, and across Sudan, please visit our blog and sign up for our email list.

From Learning To Action

Our free global event turns everyday runs, bike rides, and walks into lifesaving support. Every mile you put in and dollar you raise helps fund emergency aid, healthcare, and education programs led by Sudanese heroes. We also have an option where you can skip the exercise and just fundraise. Every dollar raised makes a difference.

Checks can be made payable to Operation Broken Silence and mailed to PO Box 770900 Memphis, TN 38177-0900. You can also donate stock or crypto. Operation Broken Silence a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Donations are tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law. Our EIN is 80-0671198.

The Nuba Mountains

The history of the geographic region known as the Nuba Mountains stretches back thousands of years. This overview focuses on the time period after Sudan’s independence in 1956.

Photo: Traditional homes (tukuls) during the rainy season in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan. (Operation Broken Silence)

This historical overview provides a contextual background for understanding the issues Operation Broken Silence works on. It is part of our resource list for students, teachers, and the curious and was last updated January 2024. For more information about what's happening in Sudan and our work, please sign up for our email list.

Introduction

While the history of the Nuba Mountains stretches back thousands of years, this overview focuses on the time period after Sudan’s independence in 1956. A chronological examination of the Nuba region in the contemporary era can be broken out into six main periods:

Pre-Modern & Colonial Background: 200 BCE-1956 CE

Cultural Oppression: 1956-1972

The Beginnings of the Second Sudanese Civil War: 1973-1988

Nuba Face A Genocide By Attrition: 1992-2004

Peace Agreement & South Sudan Partition: 2005-2010

Second War & Genocide: 2011-2019

Since Operation Broken Silence’s primary Sudanese partners work in the Nuba Mountains, a summary of the current situation is provided at the end as well.

Map: Location of Nuba Mountains. (Operation Broken Silence)

Pre-Modern & Colonial Background: 200 BCE-1956 CE

The Nuba Mountains have an ancient history, with the first known mention of the African tribes living here and other nearby areas dating to around 200 BCE by Greek scholars Eratosthenes and Strabo.

Although this geographic area has been inhabited for millennia, little direct documentation of life here is known to have been recorded before the 1900s. This undocumented history may have roots in just how isolated the region has always been; even today, the Nuba Mountains remains one of the most isolated and marginalized regions of Sudan.

This isolation does not remove the historical causes of trouble in the region. Sitting directly on the religious, ethnic, and political border of present-day Sudan and South Sudan, this demarcation highlights the roots of historical grievances and, more recently, north-south civil wars and two attempted genocides against the Nuba people by national military regimes in Khartoum.

Photo: One of the first photographs taken of the Nuba people in eastern Kao-Nyaro in 1949. (George Rodger)

The Nuba Mountains are inhabited by roughly 100 African tribes who have been referred to collectively as Nuba for centuries. These tribes are likely remnants of previous, larger tribal groups of varying languages and cultures who Eratosthenes and Strabo briefly referred to. Interestingly, until contemporary times, people living in the Nuba Mountains used their tribal name and didn’t really consider themselves to be Nuba. Famous Nuba leader Yousif Kuwa Mekki (1945-2001) mentioned this in the last interview he gave before his passing:

“It is one of the funniest things: when you were in the Nuba Mountains, you just knew your own tribe. We for example were Miri. So if we were asked: ‘Who are the Nuba?’ we would try to say: ‘The other tribes - but not us.’ Only when we came out of the Nuba Mountains, to the north or south or west, we learned that we are all Nuba.”

Photo: An artistic rendering of British colonial troops fighting in Sudan, circa 1898. (Canva Pro)

Today, virtually all of the people living here identify with their tribe and also collectively identify as Nuba. Estimations vary wildly; however, it is generally thought that roughly 45% of the Nuba people are Christian, making the mountains home to the largest community of Christians in Sudan. Other religious affiliations include 45% of the population identifying as Muslim, with the remaining 10% following local tribal regions or identifying with no religion at all.

For centuries, the Nuba Mountains have been considered a refuge for members of African tribal groups fleeing Arab slave raiders and oppression from the north. This historical reality helped cement core aspects of Nuba identity and culture that survive to this day, including tolerance, community, and an openness to the oppressed and general suspicion of non-African outsiders.

In 1899, the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium administrated Sudan as a colony. The joint British and Egyptian colonial government invested heavily in the Arab-dominated central and eastern parts of the country. Like much of the rest of Sudan, the Nuba Mountains were marginalized and ignored. British colonial troops tried to keep separate nearby Arab tribes who were hostile toward the Nuba. At various points though, the British found themselves at odds with all sides in the region.

Cultural Oppression & Rights Removals: 1956-1972

Following Sudan's independence from British and Egyptian colonial rule on January 1, 1956, the Nuba people began to witness growing tension with Arab-dominated governments in Khartoum. The violent ideologies of Arabization and Islamization gained stronger traction in Sudan’s powerful center. Government policies leading up to the 1970s saw the Nuba people become directly oppressed by Islamic Arab elites in Khartoum. Although successive governments pushed for an Arab-dominated country, relations between many African Nuba tribes and nearby, tolerant Arab tribes actually improved during this time period.

Photo: Jazira lives in the eastern Kao-Nyaro region of the Nuba Mountains, which has been targeted for Islamization and Arabization by the Sudanese government for decades. She is nominally Muslim and can speak Arabic, but mostly uses her tribal language. Government-funded childhood education is largely non-existent in Kao-Nyaro which, interestingly, has helped Nuba tribes in Kao-Nyaro maintain their identity. (Operation Broken Silence)

The First Sudanese Civil War began in 1955. The war itself had little direct impact on the Nuba Mountains; however, as Sudanese politics in Khartoum drifted toward extremism during the war, the Nuba people began to face increasing oppression that set the stage for two devastating wars and genocides in their homeland.

While the severity of the Sudanese government’s oppression varied at the local level, there are two primary areas that played critical roles: pressure on traditional Nuba culture and land seizures. Many of these pressures on Nuba culture at this time include actions which fit into the 10 Stages of Genocide, a processual model that aims to demonstrate how the crime of genocide is committed.

Government Attempts To Erase Nuba Culture

Khartoum’s oppression of traditional Nuba culture included attempts to force name-changes (from local names to Arab ones) and replace tribal languages with Arabic. Elements of the Sudanese government and Islamic political allies in Khartoum pushed an intolerant strain of Islam onto the Nuba people.

These colonizing efforts achieved mixed results. Arabic was largely adopted as a communication language, but virtually all Nuba tribal languages remain in use. A sizable number of the Nuba people consider themselves Muslim, but Nuba Muslims and Christians live largely in harmony to this today.

Government & Arab Tribal-Backed Land Seizures

The Nuba Mountains and surrounding areas are home to some of the most fertile farmland in Sudan. The national government introduced mechanized farming in 1968, which degrading security in the region further. Some Arab tribes near the Nuba Mountains who aligned more closely with Khartoum soon found their traditional grazing and watering routes blocked by large-farms built with the support of the government.

With nowhere to go, Arab tribes such as the Baggara began to use Nuba farmland —without permission— that they traditionally stayed away from. This heightened tensions between the Nuba people, Khartoum, and some Arab tribes at odds with the Nuba.

In 1970, the Sudanese government introduced the Unregistered Land Act. This law effectively abolished communal land ownership and was an attempt to destroy the centuries-long tradition of Nuba tribes considering the farming areas around the Nuba Mountains as belonging to their communities. It stipulated that all lands not privately owned and registered would automatically belong to the government in Khartoum.

Results

By the 1970s, it was clear to Nuba leaders that a systematic campaign to Arabize and Islamize their homeland was underway. Nuba tribes began to put aside the few differences they had and move toward deeper unity. Nuba political parties and social groups emerged that attempted to solve regional issues through the lens of a broader Nuba identity.

The 1972 Addis Ababa Peace Agreement ended Sudan's civil war in the south. The agreement granted significant regional autonomy to southern Sudan. It also promised the Abyei area, located to the west of the Nuba Mountains, the right to hold a referendum on remaining a part of northern Sudan or joining the newly formed southern region. Little changed in the Nuba Mountains though. In the coming years, Khartoum’s oppression only intensified as Sudanese politics was pushed into extremism.

Photo: Displaced Nuba children and women follow well-worn paths deeper into the Nuba Mountains after receiving news of regime-backed, Arab paramilitary forces nearing their farmland. Mountain paths such as these have now existed for decades and are well-known to Nuba communities. (Operation Broken Silence)

Photo: Sudanese political leader Jaafar Nimeiry in 1983. In his second presidential tenure, Nimeiry caved to Islamists in hopes of staying in power, paving the way to the Second Sudanese Civil War and the 1985 coup that removed him from power. (US Defense Department)

The Beginnings of the Second Sudanese Civil War: 1973-1988

In 1978, large quantities of oil were discovered in the southern Sudan. Hungry for cash and power, Sudanese government leaders swiftly attempted to seize control of these areas. This violated the 1972 Addis Ababa Peace Agreement. Meanwhile, in Khartoum, Arab-Islamic extremists were on the verge of seizing control of the central government.

By 1983, extremist political power had grown so much in the north that President Nimeiry, desperate to hold onto power, declared all of Sudan an Islamic state and made the fateful decision to terminate southern autonomy. Southern and Nuba leaders had watched with growing apprehension for years as the fundamentalists consolidated power in Khartoum. Now it was clear that the violent ideology building in the north would soon be unleashed against the Nuba Mountains and all of southern Sudan.

The Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) began forming in the south almost immediately. Southern soldiers mutinied across Sudanese government ranks and returned to southern Sudan to prepare for the inevitable northern invasion. SPLA forces seized large swaths of rural areas in southern Sudan.